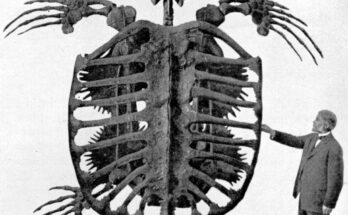

Unveiling Fossilized Bird Feathers from the Green River Formation: A Detailed Tutorial on Preservation, Anatomy, and Paleontological Insights

Introduction to Fossilized Bird Feathers

The image showcases a remarkable pair of fossilized bird down feathers from the Eocene epoch, held delicately in a hand to reveal both the positive (part) and negative (counterpart) impressions split from a single slab. Originating from the renowned Green River Formation in Wyoming, USA, these specimens date back approximately 50-52 million years, preserved in fine-grained limestone that captures exquisite details of ancient avian plumage. Down feathers, unlike the structured contour feathers used for flight, served primarily for insulation in early birds, lacking a prominent central shaft (rachis) but featuring soft, fluffy barbs radiating from a basal calamus. This tutorial-style guide explores these fossils step by step, from visual identification and anatomical breakdown to preservation mechanisms, historical context, and their significance in understanding avian evolution. Designed for paleontology enthusiasts, students, or collectors, this post provides a professional resource for analyzing similar compression fossils, whether sourced from commercial sites like eBay or Etsy, or studied in museums such as the Field Museum.

Observe the overall presentation: The left fossil displays a dark blue-black carbonized film representing the organic residue of the feather’s keratin, while the right shows a lighter yellowish impression with faint oxidized outlines, typical of split slabs where the feather was compressed between sediment layers. Measuring around 5-7 cm (2-3 inches) in length based on hand scale, these elongate, oval shapes taper to a point, with fine, parallel barbs creating a pinnate-like venation appearance that can mimic plant leaves at first glance. The matrix rock, a light beige shale, exhibits natural fractures and mineral staining from iron oxides, enhancing the visual contrast. Such fossils form in anoxic lake bottoms, where rapid burial prevented decay, making the Green River Formation a lagerstätte (exceptional fossil site) for Eocene biodiversity.

Step 1: Visual Identification and Differentiation – Recognizing Feather Fossils

Begin your analysis like a paleontological identification tutorial: Distinguish these as bird feathers by their symmetrical barb structure radiating from a subtle central axis, unlike the irregular venation of plant leaves (e.g., ferns with pinnate veins branching at angles). The positive side (left) retains carbonaceous material, appearing darker due to kerogen preservation, while the counterpart (right) is an imprint molded by the feather’s form, often with iridescent sheens from mineral replacement like pyrite or siderite. Key diagnostics include the absence of a rigid rachis—characteristic of down feathers for thermoregulation—and fine barbules (microscopic hooks) implied by the preserved texture, though not visible without magnification.

To differentiate from mimics: Compare to fossil leaves, which often show midrib thickening or secondary veins looping to margins (brochidodromous pattern), absent here. Use a 10x loupe to spot barb details; in photos like this, zoom reveals parallel striations typical of avian keratin rather than vascular bundles. For provenance, Green River feathers are commonly 1-3 cm long, from unidentified shorebirds or songbirds in a subtropical lake ecosystem. If collecting, note ethical sourcing—many are from private quarries like Fossil Lake, with COAs (Certificates of Authenticity) verifying age and locality.

Step 2: Anatomical Breakdown – Understanding Feather Structure in Fossils

Proceed as in an avian paleobiology tutorial: Dissect the feather’s components. The calamus (base) is subtly visible as a narrowed point, anchoring to skin follicles in life. The vane comprises barbs—slender filaments branching symmetrically—interlocked by barbules for fluffiness in down, aiding insulation for Eocene birds in variable climates. In the fossil, barbs appear as fine lines (0.1-0.5 mm apart), preserved via carbonization where organic matter converts to a thin film under pressure.

Compare to modern analogs: Think pigeon or duck down, but scaled down for small Eocene avians. Fossilization alters color—original pigments (melanosomes) may yield black or iridescent hues, as seen in the blue tone, potentially indicating eumelanin preservation. Advanced analysis: Use SEM (scanning electron microscopy) to reveal melanosome shapes for color reconstruction—rod-like for black, spherical for iridescent. In this specimen, the split reveals 3D depth, with the positive showing relief and the negative a mold, ideal for casting replicas.

Step 3: Preservation Mechanisms – How Feathers Fossilize

Explore taphonomy like a fossilization tutorial: Green River feathers owe their detail to lacustrine (lake) deposition in anoxic, varved shales—alternating layers of organic-rich mud that buried remains quickly, inhibiting bacterial decay. Compression flattens the feather, creating part-counterpart pairs when slabs split along bedding planes. Mineralization involves pyrite (fool’s gold) or calcite infilling voids, producing the colorful patina seen here—blue from carbon, yellow from iron oxides.

Preparation tips: To split slabs safely, use chisels or freeze-thaw methods; protect with consolidants like Paraloid B-72. For display, mount in shadow boxes to prevent UV fading. Rarity factor: While Green River yields millions of fish fossils, bird feathers are scarce (less than 1% of finds), making these valuable for study.

Step 4: Historical Discovery and Geological Context – The Green River Legacy

Trace origins historically: The Green River Formation, spanning Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado, was first explored in the 1800s during the Hayden Surveys, with bird fossils noted by 1870s paleontologists like O.C. Marsh. Feather discoveries ramped up in the 20th century via quarries like Fossil Butte, with modern digs (e.g., 2022 YouTube excavations) revealing pristine examples. As of 2025, sites like Fossil Lake continue yielding feathers, contributing to avian evolution studies post-K-Pg extinction.

Ecosystem reconstruction: Eocene Green River was a series of tropical lakes with palms and crocodiles; birds like these likely died from algal blooms or predation, sinking to oxygen-poor depths.

Step 5: Paleontological Significance and Modern Applications – Insights into Avian Evolution

Today, these feathers illuminate bird diversification after dinosaurs, showing primitive down structures predating modern neognaths. In museums, they’re displayed alongside full skeletons; for researchers, melanosome analysis via Raman spectroscopy reveals colors, aiding phylogenetic trees.

Collecting advice: Acquire from reputable sources with locality data; values range $50-200 for small slabs. Ethical note: Support public lands preservation amid 2025’s increased fossil tourism.

In conclusion, these Green River feather fossils bridge ancient skies to modern understanding, offering endless tutorial potential for paleobiology. Use this guide to identify and appreciate your own finds.