Behind the Scenes: Triceratops Skull Preparation – A Professional Tutorial on Anatomy, Conservation Techniques, and Recent Discoveries

Introduction to Triceratops Fossil Preparation

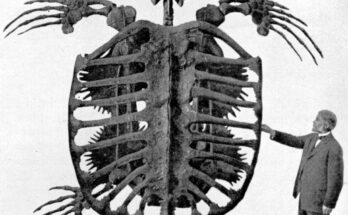

The image captures an intimate behind-the-scenes moment in a fossil preparation laboratory, where a massive Triceratops horridus skull dominates the frame, mounted on a sturdy metal stand amid scattered tools, protective bags, and a humidity control cylinder. Standing proudly beside it is a preparator—clad in a black t-shirt featuring a subtle dinosaur motif, jeans, and sneakers—his tattooed arm relaxed in his pocket, exuding the quiet expertise of someone deeply immersed in paleontological work. The industrial setting, with overhead lighting, open garage doors, and shelves of equipment, evokes the meticulous craft of transforming raw fossils into scientific treasures. Triceratops horridus, the iconic three-horned herbivore of the Late Cretaceous (68-66 million years ago), reached lengths of 9 meters (30 feet), heights of 3 meters (10 feet) at the shoulder, and weights up to 12 tons, making its skull—a robust structure up to 2.5 meters (8 feet) long—one of the most challenging and rewarding specimens to prepare. This tutorial-style guide walks you through the process step by step, from identification to advanced conservation, drawing on techniques used in labs like those at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS) or the Royal Tyrrell Museum. Ideal for aspiring paleontologists, museum educators, or enthusiasts, it equips you to appreciate the labor-intensive journey from field discovery to exhibit-ready artifact, especially timely with 2025’s groundbreaking finds.

Begin by orienting yourself to the workspace: The skull’s prominent brow horns (up to 1 meter/3.3 feet long) curve upward, the nasal horn projects forward, and the expansive frill (parietal-squamosal shelf) shows matrix remnants, indicating ongoing cleaning. Tools like air scribes (implied by hoses) and the visible humidifier maintain optimal conditions to prevent cracking in hygroscopic bone. This setup reflects standard prep labs, where relative humidity is controlled at 40-50% to mimic the fossil’s depositional environment.

Step 1: Specimen Identification – Distinguishing Triceratops horridus

Approach identification systematically, as in a field paleontology tutorial: Start with gross morphology. Triceratops horridus is diagnosed by its three facial horns—two supraorbital (above the eyes) and one epinasal (on the nose)—and a solid, fenestrated frill lacking the elongated squamosal hooks of relatives like Torosaurus. In the image, measure visually: The skull spans roughly 2 meters (6.5 feet) across the frill, typical for adults, with a beak-like rostrum for cropping ferns and cycads. Note the elliptical orbits for binocular vision, aiding predator detection, and the rough, vascularized bone texture suggesting keratin sheaths on horns for added length and protection.

Differentiate from T. prorsus (straight nasal horn) or juveniles (shorter, more rounded features). Use comparative references: Scan for pathologies like healed fractures on the frill, common from intraspecific combat. In labs, initial ID involves photography and 3D modeling software like Blender or CT scans to map completeness—here, the skull appears 85-90% intact, with gaps filled later via mirroring techniques. For authenticity, cross-reference quarry data; this specimen likely hails from the Hell Creek Formation in Montana or North Dakota, hotspots for ceratopsian finds.

Step 2: Anatomical Dissection – Key Cranial and Sensory Features

Delve deeper with an osteological tutorial: The cranium houses a braincase with poor olfactory bulbs, indicating reliance on vision and low-frequency hearing for herd communication rather than scent-tracking. Examine the jaw: Battery-like dental rows (up to 800 teeth) enabled shearing tough vegetation, with a parrot-like beak for initial cropping. The frill, weighing 200-300 kg (440-660 lbs) alone, featured blood vessels for possible thermoregulation or display, evidenced by vascular grooves visible in the photo.

Focus on horns: Composed of dense cortical bone over a spongy core, they grew continuously, with growth rings analyzable via histology for age (up to 20-30 years). In the image, note matrix adhering to the nasal horn—preparators use this to infer orientation. For hands-on study, employ calipers for measurements: Brow horns average 80-100 cm (2.6-3.3 feet). Modern analogs like rhinos inform function: Defense against Tyrannosaurus or intra-species ramming, with frill scars suggesting battles. Advanced: Use micro-CT for internal sinuses, revealing air-filled chambers for weight reduction.

Step 3: Preparation Techniques – From Field Jacket to Finished Mount

Transition to practical conservation, mirroring lab workflows: Fossil prep begins post-excavation with mechanical removal of overburden using air abrasives or pin vices—hoses in the background suggest this phase. Consolidate fragile bone with Paraloid B-72 resin (1-5% acetone solution) to prevent flaking, applied via brush as seen in similar setups. The humidifier cylinder maintains equilibrium moisture, crucial for hygroscopic fossils like this, avoiding cracks during transport (e.g., the DMNS’s 2025 North Dakota haul).

Mold and cast gaps with silicone for replicas, then articulate on aluminum armatures like the stand here. Chemical cleaning (e.g., dilute formic acid for matrix) follows, with safety gear implied. Document via photogrammetry for digital archives. Time estimate: 500-1,000 hours for a skull this size, involving iterative stabilization. Tip: In humid climates, seal with microcrystalline wax post-prep.

Step 4: Historical Context and 2025 Discoveries – Evolving Knowledge

Contextualize historically: First described in 1889 by O.C. Marsh from Denver quarry fragments, over 50 skulls are known, mostly from Hell Creek. Recent 2025 highlights include DMNS’s October discovery near Marmarth, North Dakota—a near-complete skull, jaws, and neck unearthed by interns, now in prep (echoing this image’s vibe). Phillips’ November auction of a juvenile specimen—the first intact young Triceratops—reveals ontogenetic changes, like softer horns. Augustana College’s rib and frill fragments from Illinois badlands add to growth studies. These finds, prepped in labs like the imaged one, use AI-enhanced scanning for rapid analysis.

Step 5: Scientific and Cultural Significance – From Lab to Legacy

Conclude with broader impact: Prepared skulls like this fuel research on ceratopsian evolution, herd dynamics, and K-Pg extinction, with frill vascularity hinting at social signaling. Culturally, they star in exhibits (e.g., DMNS’s “Prehistoric Journey”) and media, inspiring STEM. For preparators like the one photographed, it’s a blend of artistry and science—preserving history one chisel mark at a time.

Ethical note: Provenance tracking combats illicit trade. In 2025, amid climate-driven erosion exposing new sites, such labs safeguard irreplaceable heritage.

This tutorial demystifies the prep process, inviting you to the lab’s frontlines. Next time you see a gleaming Triceratops mount, recall the unseen hands—and humidity gauges—behind it.