Fossils That Still Contain Soft Tissue

One of the most astonishing discoveries in modern paleontology is the preservation of soft tissue—including blood vessels, cells, collagen, and sometimes even proteins—in fossils that are tens to hundreds of millions of years old. Traditionally, soft tissues like muscles, skin, organs, and cells were thought to decay rapidly after death, leaving only hard parts like bones or shells to fossilize. However, since the early 2000s, researchers have found flexible, original biological materials in dinosaur bones and other ancient specimens, challenging assumptions about decay rates and preservation mechanisms.

These finds often involve demineralizing (dissolving away the mineralized bone) to reveal flexible structures inside. While rare, they occur in various environments and taxa, from dinosaurs to marine invertebrates.

Iconic Example: Mary Schweitzer’s T. rex Discovery (2005)

Paleontologist Mary Schweitzer and her team made headlines when they reported flexible blood vessels, osteocytes (bone cells), and collagen in a 68-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex femur from Montana. After treating the bone with weak acid, the mineral dissolved, leaving stretchy, transparent vessels and fibrous matrix that resembled fresh tissue. Biochemical tests confirmed collagen proteins similar to those in modern birds (dinosaurs’ descendants).

This sparked debate but has been replicated in multiple specimens. Iron from hemoglobin may act as a preservative by crosslinking proteins and preventing decay.

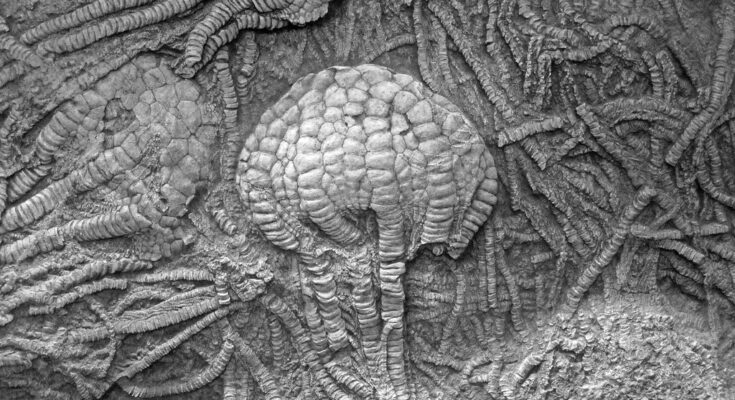

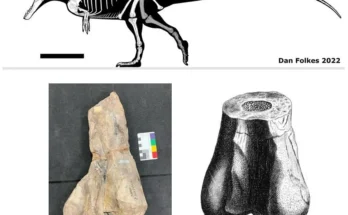

Here are images of soft tissue structures from dinosaur fossils, including blood vessels and cells from T. rex and related finds:

Microscopic views of preserved cells and vessels:

Other Notable Soft Tissue Fossils

Soft tissue preservation isn’t limited to dinosaurs. Exceptional cases include:

- Borealopelta nodosaur (mummified armored dinosaur, ~110 million years old): Skin, armor, and stomach contents preserved, one of the best “dinosaur mummies.”

- Cambrian soft-bodied fossils (e.g., Qingjiang biota, China): Thousands of specimens with eyes, guts, brains, and other organs from ~518 million years ago, rivaling the Burgess Shale.

- Crab with mineralized gills and stomach (75 million years old, Cretaceous): Rare preservation of internal soft parts in a marine crustacean.

- Marine crocodilian femur: Original bone proteins detected via antibodies.

- Insects and other organisms in amber: Fully intact soft bodies, including muscles and organs, preserved in resin (often millions of years old).

Amber-preserved insects with detailed soft tissue:

More examples of exceptionally preserved soft-bodied fossils:

How Does Soft Tissue Survive?

Several mechanisms explain these rare preservations:

- Iron-mediated crosslinking: Iron from blood may stabilize proteins against decay.

- Rapid burial in low-oxygen environments: Prevents bacterial breakdown.

- Mineral infiltration: Bone matrix or surrounding sediment protects and stabilizes tissues.

- Exceptional lagerstätten (fossil sites): Like Burgess Shale or amber deposits, where fine-grained sediments or resin entomb organisms quickly.

Recent studies (including 2025 research from NC State) show soft tissue in various dinosaur species, ages, and burial settings—suggesting it’s more common than thought, especially in well-preserved bones.

These discoveries open doors to studying ancient proteins, diseases, and evolution at the molecular level. For deeper exploration, watch videos on Schweitzer’s work or soft tissue preservation, such as documentaries from National Geographic or Smithsonian channels explaining the T. rex find and its implications.

Soft tissue fossils continue to surprise scientists, revealing that Earth’s ancient life left more than just bones behind—they left glimpses of the living!