Fossils vs Bones: What Is the Difference?

Introduction

People often refer to dinosaur skeletons in museums as “bones,” but most are actually fossils. The key distinction lies in age, preservation, and composition. A bone is the living or recently deceased hard tissue from a vertebrate’s skeleton, made of organic materials like collagen combined with minerals like calcium phosphate. A fossil, by contrast, is any preserved evidence of ancient life—typically over 10,000 years old—that has undergone natural processes turning it into rock-like material or impressions.

While bones can become fossils through fossilization, not all bones are fossils, and most museum-displayed “dinosaur bones” are mineralized replicas of the original structure rather than unaltered bone.

For a clear visual explanation of how bones turn into fossils, watch this educational video: Why Don’t All Skeletons Become Fossils? | STUFF from the Smithsonian.

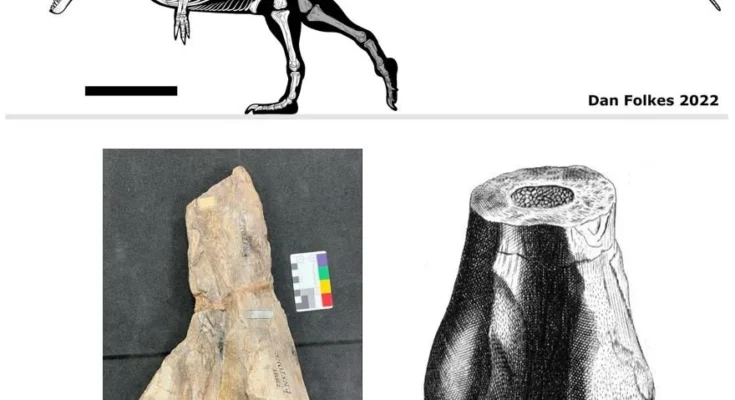

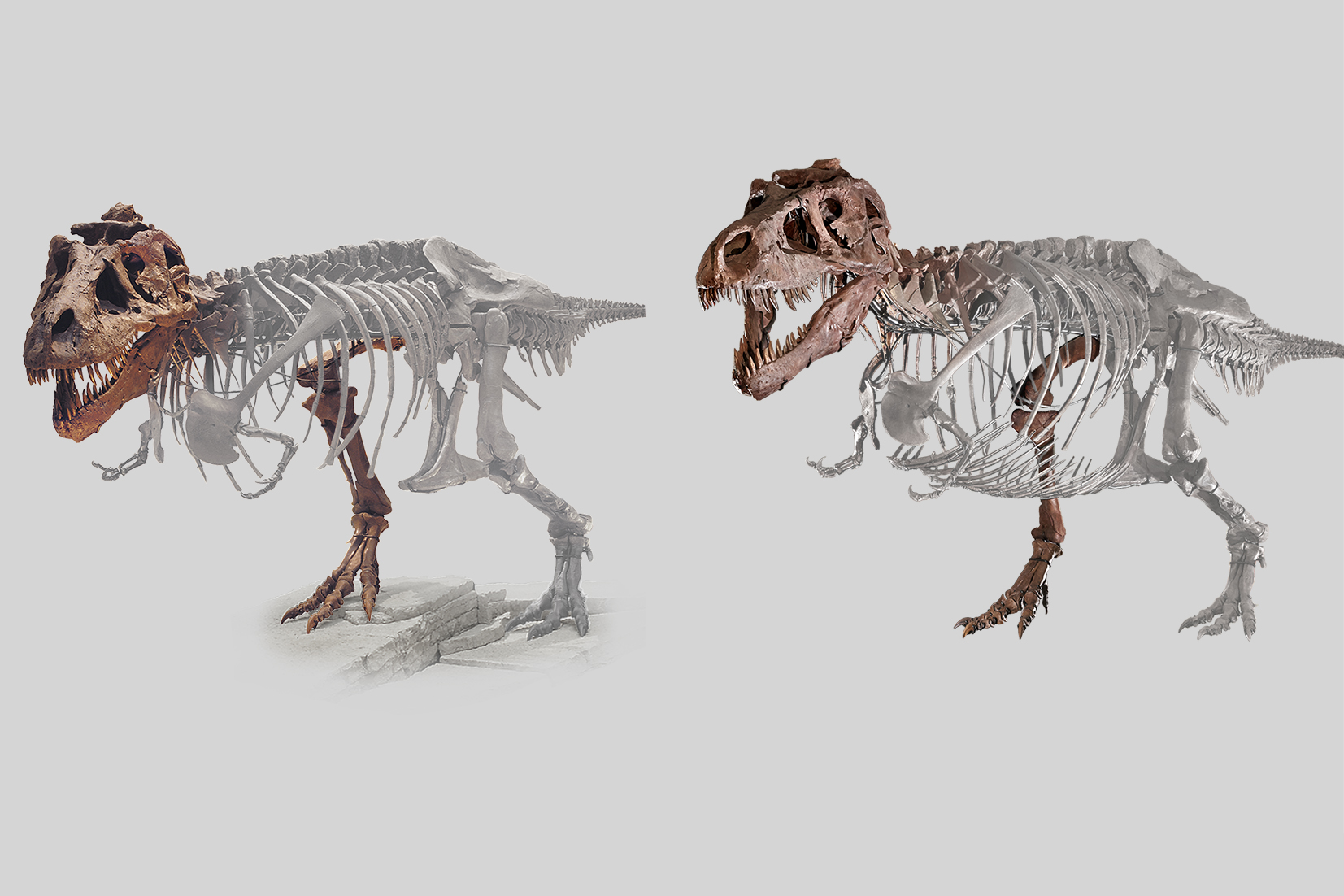

(Side-by-side comparison of a modern bare-bone T. rex skeleton cast versus a fossilized brown specimen, highlighting color and texture differences.)

What Is a Bone?

Bones are living tissues in vertebrates (animals with backbones) that provide support, protect organs, store minerals, and produce blood cells. Fresh bones contain:

- Organic components (about 30–40%): collagen protein for flexibility and toughness.

- Inorganic minerals (about 60–70%): hydroxyapatite (calcium phosphate) for hardness.

- Living cells, blood vessels, and marrow.

After death, soft tissues decay quickly, but bones can persist for hundreds to thousands of years if protected from weathering—though they remain “bone” material until fossilization begins.

(Modern mammal jawbone showing natural bone color and structure, compared to a fossilized counterpart below it.)

What Is a Fossil?

A fossil is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of an organism from a past geological age, usually more than 10,000 years old. Common types include:

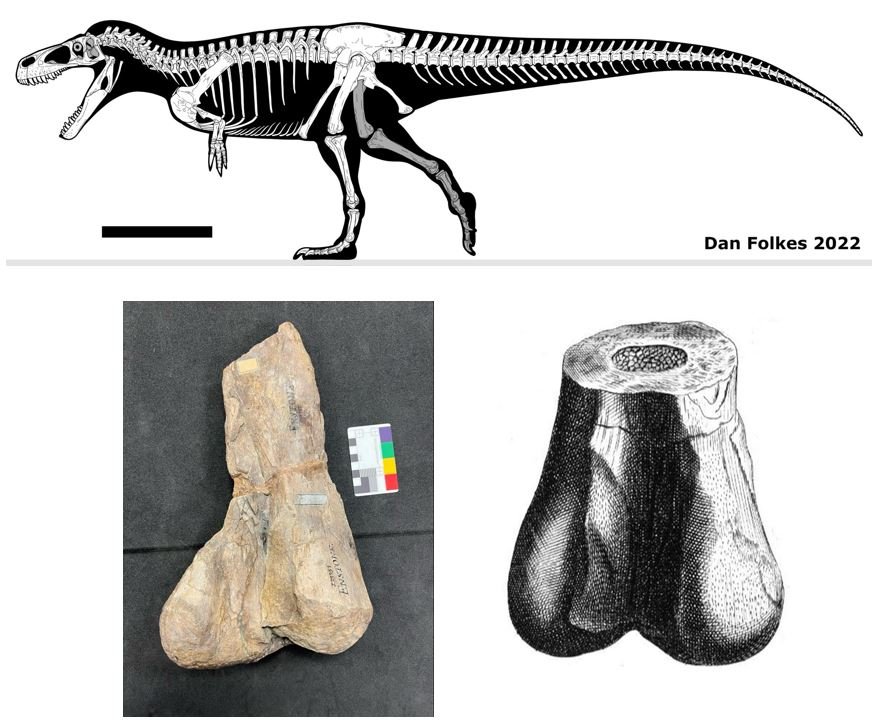

- Body fossils: Actual parts of the organism, like mineralized bones, teeth, shells, or petrified wood.

- Trace fossils: Evidence of activity, such as footprints, burrows, or coprolites (fossilized dung).

Fossilized bones form through processes like permineralization (minerals fill pores) or replacement (original material dissolves and is replaced by minerals), turning the porous bone structure into rock while preserving shape and internal details.

(Close-up of permineralized fossil bone showing colorful mineral infilling in the original porous structure.)

(Microscopic view of permineralized dinosaur bone, revealing mineral-filled pores and preserved cellular patterns.)

Key Differences Between Fossils and Bones

| Aspect | Bone (Modern/Recent) | Fossil (Typically Ancient) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Recent (days to thousands of years) | Usually >10,000 years old |

| Composition | Organic collagen + mineral hydroxyapatite | Mostly replaced or filled with minerals (rock-like) |

| Organic Material | Present (collagen, cells) | Mostly gone; rare exceptions in exceptional preservation |

| Weight/Texture | Lighter, porous, may feel greasy | Heavier, denser, often stone-like; tongue may stick slightly due to porosity |

| Color | White to ivory, may yellow with age | Often brown, black, red, or mineral-stained |

| Preservation | Decays without burial | Requires rapid burial and mineralization |

A quick field test (used cautiously): A fossil bone’s porous surface may make your tongue stick slightly when licked, unlike a smooth rock.

(Side-by-side of a fossilized dinosaur femur fragment showing rock-like texture versus a modern bone equivalent.)

How Bones Become Fossils

Fossilization is rare—most remains decay completely. Key steps:

- Rapid burial in sediment (sand, mud, or volcanic ash) protects from scavengers and oxygen.

- Soft tissues decompose, leaving hard parts.

- Groundwater carries minerals that seep into bone pores (permineralization), filling voids and hardening the structure.

- Over millions of years, original organic material may dissolve and be replaced.

In rare cases (e.g., frozen mammoths or amber), original material persists with little change.

(Ancient insect perfectly preserved in amber, an example of exceptional fossilization retaining original organic material.)

(Close-up of an insect fossil in amber, showing detailed preservation of wings and body without heavy mineralization.)

Conclusion

The main difference boils down to time and transformation: bones are biological tissues from living or recently dead organisms, while fossils are geological records of ancient life, where original bone has typically been mineralized into stone. Understanding this helps appreciate why museum specimens are often casts or heavily prepared fossils rather than “fresh” bones. Fossils provide irreplaceable evidence of Earth’s history, revealing evolution, ancient environments, and extinct species.

For more on fossilization processes, check out this video: How Fossils Form | AMNH (explains burial, mineralization, and why most bones never fossilize).