The Crushing Jaws of Prognathodon: Durophagous Mosasaurs and Their Specialized Dentition – A Museum Exhibit Tutorial

Description:

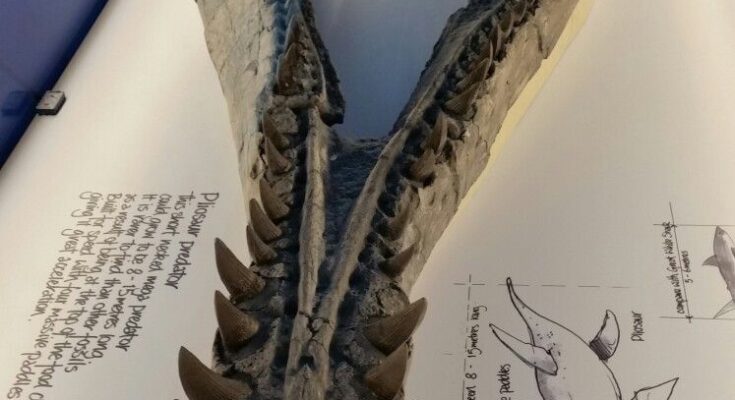

The image presents a meticulously prepared museum exhibit featuring the lower jaw (mandible) of a large mosasaur, likely from the genus Prognathodon, displayed in a glass case with dramatic blue lighting. The robust, V-shaped mandible is lined with massive, conical, bulbous teeth adapted for crushing hard-shelled prey. Accompanying the fossil are an informational plaque with handwritten-style text and diagrams comparing tooth morphology, plus a small mounted skull (possibly of a turtle or ammonite) for context. This professional tutorial-style guide dissects the exhibit step-by-step, suitable for educators, students, collectors, and paleontology enthusiasts. We’ll explore identification, dental adaptations, paleobiology, fossil preparation, and notable specimens to provide comprehensive insights into these apex marine predators of the Late Cretaceous (approximately 100–66 million years ago).

Step 1: Identifying the Specimen – A Prognathodon Mandible

The centerpiece is the lower jaw of a mosasaur from the family Mosasauridae, specifically attributable to Prognathodon based on the distinctive dentition: thick, robust, conical teeth with rounded crowns and minimal curvature, ideal for durophagy (shell-crushing). Prognathodon species, such as P. solvayi, P. overtoni, or P. waiparaensis, reached lengths of 10–14 meters (33–46 feet) and were among the most specialized mosasaurs.

The mandible is displayed symphysis-up (fused front end at the bottom), revealing the tooth row in natural alignment. Preservation quality suggests origin from the Maastrichtian phosphate deposits of Morocco (Ouled Abdoun or Khouribga Basin), where such jaws are commonly excavated and prepared for museums and private collections.

The plaque text appears to read: “Dinosaur Predator / This lower jaw belongs to a giant marine predator known as a mosasaur… lived 85-66 million years ago… teeth adapted to crush hard-shelled prey such as turtles and ammonites.” Diagrams illustrate tooth cross-sections and comparisons to modern analogs.

A comparable Prognathodon lower jaw exhibit:

Step 2: Dental Anatomy and Specialization – The Crushing Apparatus

Mosasaur jaws evolved diverse feeding strategies. Prognathodon stands out with durophagous dentition:

- Teeth are massive (up to 5–7 cm crown height), globular, and enamel-covered with blunt tips for distributing force without fracturing.

- Faceted wear patterns (visible on many specimens) result from grinding against shells.

- The mandible is deep and heavily ossified, supporting high bite forces—biomechanical models estimate over 10,000 newtons in large individuals.

Contrast with other mosasaurs: Mosasaurus had slicing blades; Tylosaurus featured piercing cones; Globidens possessed pavement-like molars. Prognathodon’s teeth evolved convergently with modern crab-eating sharks.

The small mounted specimen atop the case likely represents prey, such as a sea turtle skull, illustrating the predator-prey dynamic. Diagrams on the plaque show tooth insertion (thecodont, rooted in sockets) and cross-sections highlighting enamel thickness.

Close-up of Prognathodon crushing teeth:

Step 3: Paleobiology – Lifestyle of a Shell-Crushing Giant

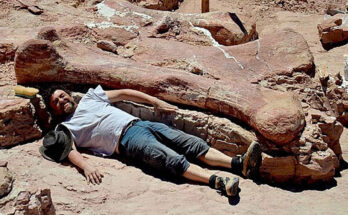

Prognathodon inhabited warm epicontinental seas during the Maastrichtian, preying on turtles, ammonites, bivalves, and nautiloids. Stomach contents from related genera confirm hard-shelled diets; one Prognathodon overtoni specimen preserved turtle remains.

As fully aquatic lizards (related to monitor lizards and snakes), they used powerful tails for propulsion and paddle-like limbs for steering. Large orbits suggest good vision in murky waters; wide gapes allowed engulfing bulky prey.

They coexisted with other mosasaurs, partitioning niches—Prognathodon as the “nutcracker” specialist. Extinction at the K-Pg boundary (66 million years ago) ended their reign.

Step 4: Fossil Preparation and Exhibit Context

Moroccan mosasaur jaws undergo extensive preparation: matrix removal with air scribes, consolidation with stabilizers, and sometimes minor restoration (e.g., reattaching teeth). The blue lighting enhances texture and mineral replacement (often phosphate-rich).

Such exhibits appear in institutions like the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, or traveling displays. The plaque’s educational style (hand-drawn diagrams) emphasizes comparative anatomy.

Another museum-grade Prognathodon jaw display:

Step 5: Notable Specimens and Modern Research

Iconic Prognathodon jaws include:

- IRSNB R12 (P. solvayi holotype, Brussels)—nearly complete skull.

- High-end commercial specimens from Morocco, often 40–60 cm mandibles.

Recent studies (e.g., 2020s CT scans) reveal internal bone structure for bite force modeling. Isotope analysis indicates cosmopolitan distribution across ancient seas.

Tutorial tip: When viewing similar exhibits, note tooth wear facets and root exposure—indicators of authenticity and use in life.

Step 6: Ethical Collecting and Appreciation

Support museums and reputable dealers with provenance. Replicas are excellent for education, preserving originals for research.

In essence, this exhibit captures the brute power of Prognathodon—a specialized hunter whose jaws turned armored prey into meals. From Cretaceous seas to modern displays, these fossils remind us of the diverse adaptations that once ruled ancient oceans.