Mastering Compositional Directional Forces: Using Arrows and Leading Lines to Guide the Viewer’s Eye in Landscapes and Still Lifes

Description:

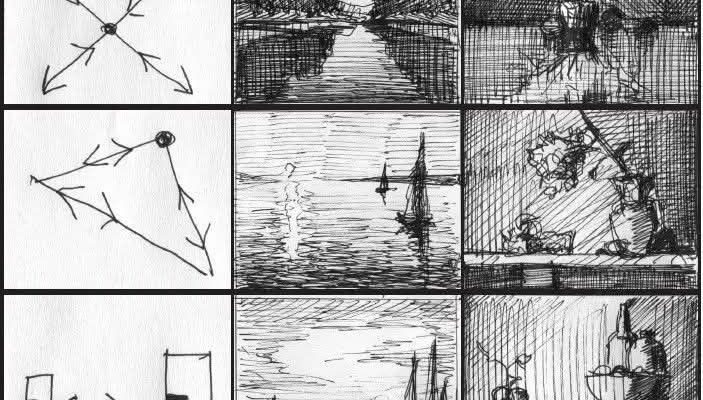

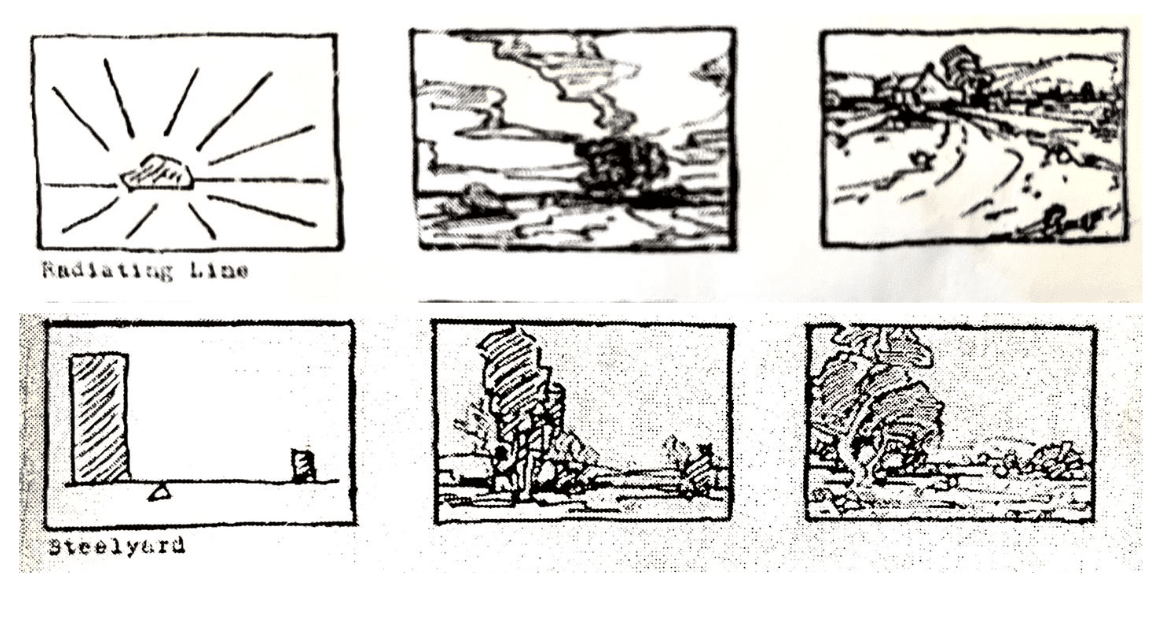

Effective composition is the backbone of powerful artwork, and one of its most dynamic tools is the strategic use of directional forces—invisible lines and arrows that guide the viewer’s eye through the piece. This classic tutorial diagram illustrates five fundamental compositional structures using simple arrow schematics alongside corresponding pencil sketches of landscapes (rivers, sailboats, horizons) and still lifes (vases with flowers, bottles, reflective surfaces). By analyzing these paired examples, artists learn how to create movement, focus, balance, and emotional impact. Ideal for beginners in drawing and painting, as well as experienced illustrators refining their skills, this guide breaks down each type to help you intentionally direct attention, avoid static compositions, and elevate your observational drawings.

Principle Overview: Directional Forces and the Viewer’s Eye

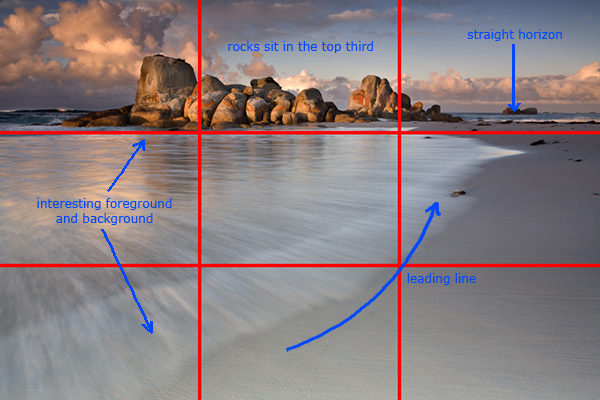

The human eye naturally follows lines, edges, and contrasts. Compositional arrows represent these “forces”:

- Strong lines pull attention.

- Converging lines create depth and focus.

- Balanced opposing forces create harmony.

- Radiating lines evoke energy or drama.

The diagram pairs abstract arrow diagrams (left column) with realistic ink/pencil renderings (middle: landscapes; right: still lifes), demonstrating universal application across subjects.

Type 1: Vertical Dominant (T-Shape) – Stability and Height Emphasis

Diagram: A central dot with arrows up/down (vertical stem) and left/right (horizontal crossbar), forming a T.

Landscape Example: Tree reflection in water—strong vertical trunk mirrored below, horizontal ripples extending sideways.

Still Life Example: Tall vase with flowers; vertical stems dominate, horizontal table edge balances.

Application:

- Creates calm, monumental feel.

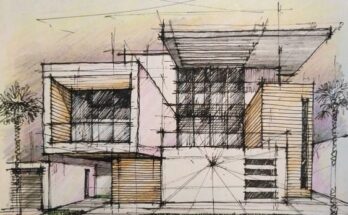

- Ideal for portraits, architecture, or solitary subjects.

- Use when emphasizing height or symmetry.

Tip: Place the vertical slightly off-center for subtle dynamism (rule of thirds).

Type 2: Diagonal Cross (X-Shape) – Dynamic Tension and Movement

Diagram: Crossing diagonals forming an X through a central point.

Landscape Example: Receding river or path flanked by trees, creating opposing diagonals toward the horizon.

Still Life Example: Flowers leaning in crossed directions, shadows intersecting.

Application:

- Introduces energy and instability—great for dramatic scenes.

- Guides eye in a zigzag, prolonging engagement.

- Common in Baroque art for narrative drive.

Tip: Balance the cross to avoid chaos; one diagonal often stronger as the primary path.

Type 3: Triangular or Pyramid – Focus and Stability

Diagram: Three arrows forming a triangle pointing downward to a base.

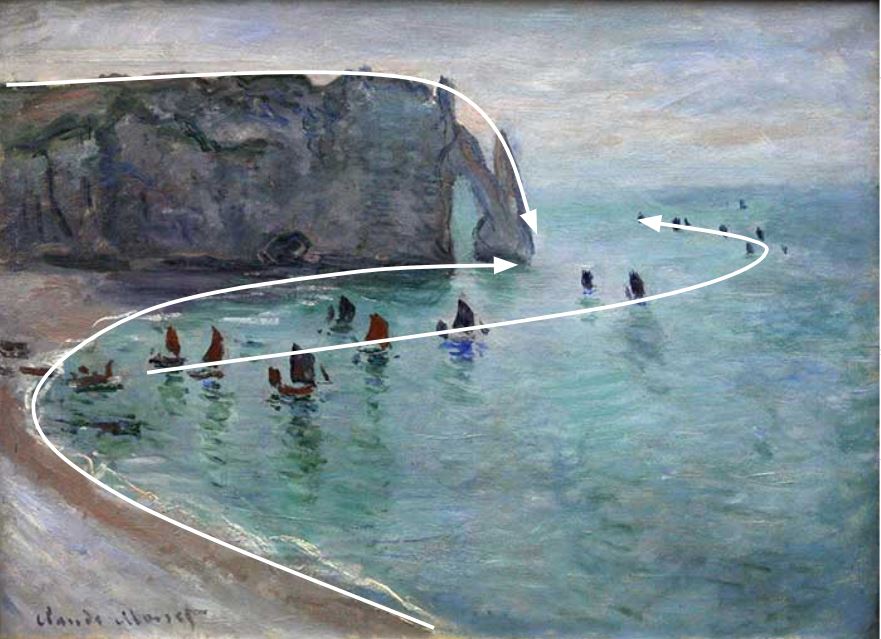

Landscape Example: Sailboats on water with smoke/masts forming triangular convergence.

Still Life Example: Vase and flowers arranged in a triangular mass, light rays converging.

Application:

- Directs eye to a central focal point (e.g., main subject at base).

- Classic Renaissance composition (Madonna pyramids).

- Provides strong unity and restful viewing.

Tip: Invert for upward energy (e.g., mountains).

Type 4: L-Shape or Right Angle – Grounding and Invitation

Diagram: Arrows forming an L with small squares (perhaps indicating masses or frames).

Landscape Example: Horizon with figure and boats; foreground elements frame an L leading inward.

Still Life Example: Table edge and objects forming an L, inviting eye into the arrangement.

Application:

- Anchors composition at corners.

- Creates a “threshold” feel—viewer enters the scene.

- Useful for asymmetrical balance.

Tip: Combine with rule of thirds for natural placement.

Type 5: Radiating or Explosive – Energy and Drama

Diagram: Multiple arrows bursting outward from a central point.

Landscape Example: Stormy sky with radiating clouds, distant ship as focal origin.

Still Life Example: Flowers exploding from vase, light rays fanning out.

Application:

- Conveys expansion, explosion, or divine light.

- High emotional impact—use sparingly to avoid overwhelming.

- Seen in Van Gogh’s starry skies or sunbursts.

Tip: Place the center off-frame for implied continuation.

Practical Tips for Applying Directional Forces

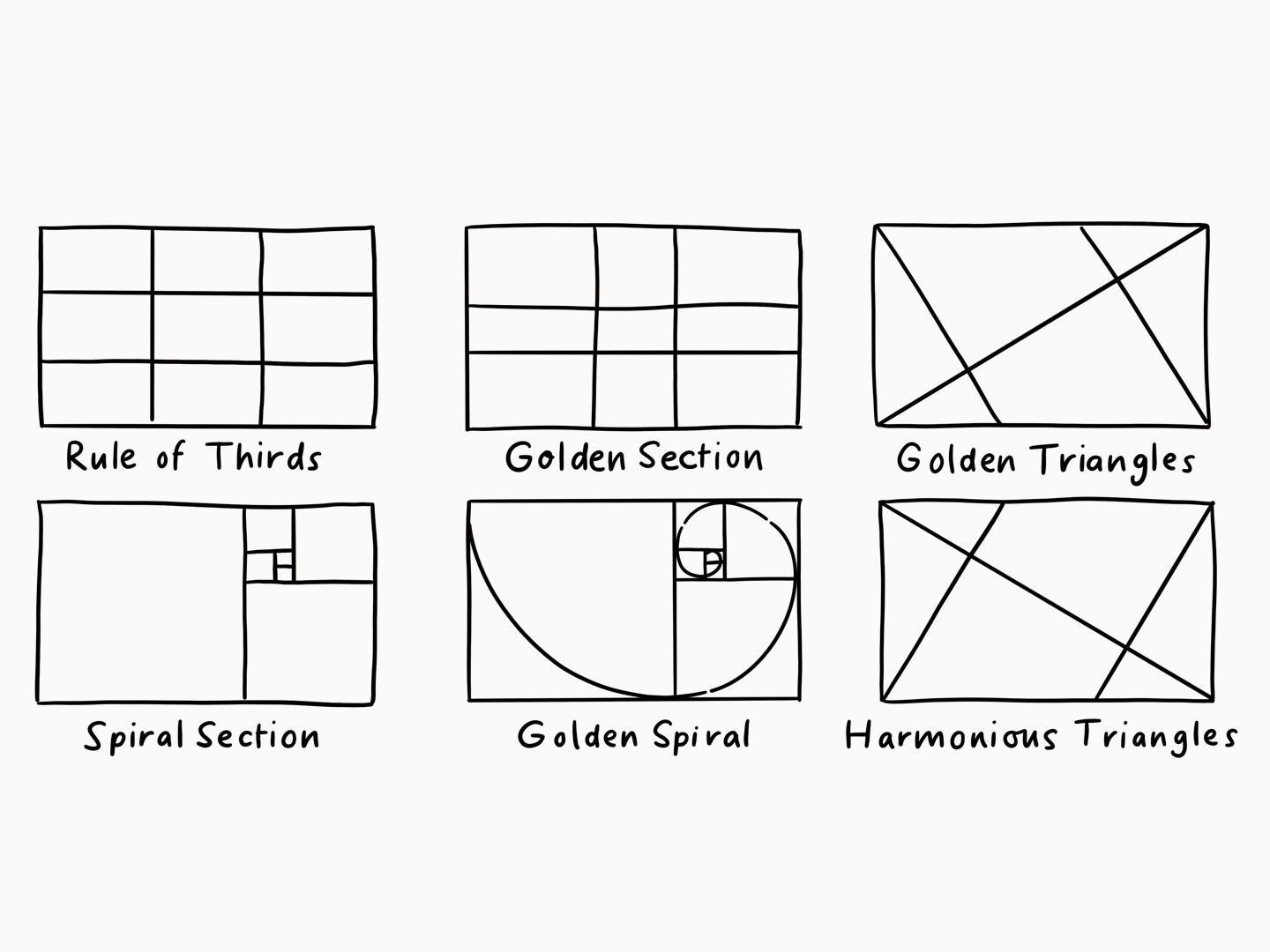

| Type | Emotional Effect | Best Subjects | Common Pitfall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical T | Calm, majestic | Trees, buildings, portraits | Too static—add subtle curves |

| Diagonal X | Tension, movement | Paths, action scenes | Overcrossing → confusion |

| Triangle | Unity, focus | Groups, central subjects | Flat base → lack of depth |

| L-Shape | Invitation, balance | Interiors, corners | Weak corner → lost eye path |

| Radiating | Energy, drama | Light sources, explosions | Overuse → chaotic |

Practice Exercise:

- Choose a reference photo (landscape or still life).

- Overlay arrows to identify existing forces.

- Sketch thumbnails testing different structures.

- Render one full drawing emphasizing your chosen type.

Conclusion: Transform Your Art with Intentional Direction

Understanding and controlling directional forces turns random sketches into compelling narratives. These five archetypes provide a toolkit for any subject—apply them consciously to guide emotion and storytelling.

Recommended Resources:

- Composition of Outdoor Painting by Edgar Payne

- Picture This: How Pictures Work by Molly Bang

- Framed Ink by Marcos Mateu-Mestre (for illustration)

Challenge: Draw a still life and landscape using each type—share your results with #DirectionalForcesArt!

Drawing Fundamentals Academy ©