Unveiling the Ankylosaurus Tail Club: From Prehistoric Weapon to Modern Cast – A Detailed Paleontological Exploration

Description:

In the fascinating world of paleontology, few dinosaur features capture the imagination quite like the tail club of the Ankylosaurus, a armored behemoth from the Late Cretaceous period. This comprehensive guide, inspired by the accompanying image, delves into the anatomy, function, historical discovery, and modern study of this remarkable structure. We’ll explore it step-by-step, much like a tutorial on understanding prehistoric adaptations, to provide a professional and thorough overview suitable for educators, students, and dinosaur enthusiasts alike. Whether you’re building a museum exhibit, writing a research paper, or simply curious about these ancient creatures, this detailed description will equip you with in-depth knowledge.

Step 1: Understanding the Ankylosaurus – An Overview of the Dinosaur

To appreciate the tail club, we must first contextualize the Ankylosaurus itself. Ankylosaurus magniventris, often referred to as the “fused lizard” due to its heavily armored body, roamed North America approximately 68 to 66 million years ago during the Maastrichtian stage of the Cretaceous. This quadrupedal herbivore measured between 6 to 8 meters (20 to 26 feet) in length and weighed an estimated 4.8 to 8 metric tons (about 5.3 to 8.8 short tons), making it one of the largest known ankylosaurids.

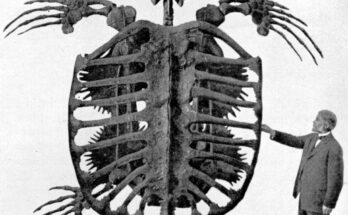

The dinosaur’s body was a fortress of natural defenses: osteoderms (bony plates) embedded in its thick skin formed a mosaic of armor across its back, sides, and even eyelids. Spikes and horns protruded from its shoulders and flanks, deterring predators like Tyrannosaurus rex. However, the crowning glory was its tail – a flexible “handle” of vertebrae culminating in a massive, bony club. This weaponized appendage, visible in the upper portion of the image as a detailed reconstruction or model, showcases the dinosaur in a dynamic pose, highlighting the club’s elevated position for swinging.

In the image, the top section depicts a lifelike model of the Ankylosaurus in mid-stride, mouth agape as if roaring a challenge. The textured skin, spiked armor, and clubbed tail emphasize its role as a defensive powerhouse. Such models are often created using fossil evidence and artistic interpretation to educate the public on how these creatures might have appeared in life.

Step 2: Anatomy of the Tail Club – Structure and Composition

The tail club, or “osteodermal club,” is composed of several fused osteoderms at the tail’s end, reinforced by ossified tendons and vertebrae. Paleontologists estimate the club’s mass at around 20 kilograms (approximately 44 pounds) in life, based on studies of well-preserved specimens like those from the Hell Creek Formation in Montana and Wyoming. However, fossilized clubs can be heavier due to mineralization – the process where groundwater deposits minerals into the bone over millions of years, turning it into a dense, rock-like structure.

Fossils reveal that the tail was divided into two parts: the proximal “handle” (made of flexible vertebrae for swinging) and the distal club (a solid mass up to 60 centimeters wide). CT scans and biomechanical analyses, such as those conducted by researchers like Victoria Arbour and Kenneth Carpenter, show that the club could generate forces equivalent to a sledgehammer blow, capable of fracturing bones or deterring attacks. One study estimated impact forces up to 2,000 newtons, enough to crush a predator’s leg.

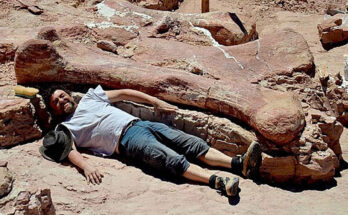

In the lower portion of the image, we see paleontologist Dr. Andrew A. Farke posing with a lightweight cast of an Ankylosaurus tail club at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology in Claremont, California. (Note: The museum is often abbreviated as the “Alf Museum,” though sometimes misspelled as “Alpha” in online references.) Dr. Farke, a renowned expert on armored dinosaurs, is shown in a museum storage area, smiling as he easily holds the cast – a replica made from materials like fiberglass or plaster to mimic the original fossil’s shape without its burdensome weight. The real fossilized club would be impossible to lift casually due to its considerable mass, often exceeding 20-50 pounds (9-23 kilograms) after mineralization, combined with its awkward shape and the fragility of ancient bone.

This contrast in the image – the full dinosaur model above and the isolated club below – serves as a visual tutorial on scale and realism, reminding us that while reconstructions bring dinosaurs to life, handling actual fossils requires specialized equipment.

Step 3: Evolutionary Purpose and Behavioral Insights – Defense, Combat, or Display?

Why did the Ankylosaurus evolve such a specialized tail? Recent research suggests multiple functions, evolving our understanding beyond simple predator defense. A 2022 study published in Biology Letters, analyzing injuries on ankylosaur fossils, proposed that tail clubs were used in intraspecific combat – battles between ankylosaurs for territory, mates, or resources. Paleontologist David Evans noted patterns of healed fractures on flanks, consistent with club strikes from rivals, rather than just predator bites.

Additionally, the tail served as a counterbalance for the dinosaur’s heavy body, aiding in stability while foraging low vegetation. In a tutorial-like simulation, imagine the Ankylosaurus swinging its tail in a 180-degree arc: muscles in the caudal vertebrae would contract, propelling the club at speeds up to 10 meters per second. This could deliver devastating blows, as modeled in biomechanical software like those used in the 2009 WIRED article on dinosaur tails.

However, not all ankylosaurs had clubs; earlier species like Nodosaurus lacked them, indicating the feature evolved later for specific environmental pressures. Footprints discovered in the Canadian Rockies in 2025 further confirm that club-tailed ankylosaurs moved in herds, potentially using their tails for group defense.

Step 4: Discovery and Fossil Record – Historical Context

The first Ankylosaurus fossils were discovered in 1906 by Barnum Brown in Montana, including partial skeletons with tail clubs. Since then, specimens like AMNH 5895 (housed at the American Museum of Natural History) have provided key insights. Self-taught paleontologists, such as Art LuJan in Texas (2019 discovery), have even uncovered potential new species with similar clubs, expanding the ankylosaur family tree.

Fossils are rare due to the dinosaur’s habitat in floodplain environments, where remains were often scattered. Modern techniques like 3D scanning allow for casts like the one Dr. Farke holds, enabling hands-on study without risking damage to originals. Museums worldwide, including the Alf Museum, use these replicas for education, research, and public displays.

Step 5: Modern Applications and Conservation – Lessons for Today

Studying the Ankylosaurus tail club isn’t just academic; it informs biomechanics, inspiring designs in robotics (e.g., flexible armored tails for exploration drones) and even sports equipment. Paleontologists emphasize ethical fossil handling: always use casts for demonstrations to preserve originals.

If you’re inspired to explore further, visit institutions like the Alf Museum or use online resources from the Royal B.C. Museum. For hands-on learning, consider 3D-printing a tail club model – start with free STL files from sites like Thingiverse, scale it accurately using measurements from Wikipedia or scientific papers, and paint it to match fossil hues.

In summary, the image encapsulates the blend of ancient power and modern science: the Ankylosaurus as a living tank, its tail club a evolutionary marvel, and Dr. Farke’s pose a reminder of human curiosity. This detailed exploration serves as your tutorial to appreciating one of nature’s most ingenious defenses.