Encountering Gastornis: The Majestic Giant Flightless Bird of the Eocene – A Guide to an Iconic Museum Fossil Exhibit

Description: An In-Depth Educational Exploration

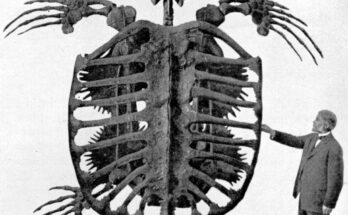

Dive into the fascinating world of prehistoric avian giants with this comprehensive tutorial-style guide to one of the most striking fossil exhibits: the skeleton of Gastornis (formerly known as Diatryma in North American specimens), a towering flightless bird from the Eocene epoch. The provided image captures a moment of pure wonder – a visitor in a yellow cardigan and dark pants stands beside the mounted skeleton, hands clasped near their face in an expression of awe and surprise. This dynamic pose highlights the sheer scale and imposing presence of the fossil, set against an elegant museum backdrop featuring arched windows, ornate railings, and natural light filtering in. Whether you’re a paleontology enthusiast, educator, student, or planning a museum visit, this guide breaks down the exhibit step-by-step, blending visual analysis, historical context, anatomical details, and scientific insights to deepen your understanding of this remarkable creature.

Step 1: Visual Analysis of the Exhibit – Capturing the Moment of Awe

Begin by closely observing the image, which perfectly encapsulates the thrill of paleontological discovery. The Gastornis skeleton dominates the frame, mounted on a black pedestal in a lifelike, upright posture with its long neck curved gracefully and massive beak tilted upward. The bird’s skull is enormous and parrot-like, with a deep, powerful beak lacking teeth – a hallmark of its adaptation. Its legs are robust and pillar-like, ending in broad, three-toed feet, while tiny vestigial wings hint at its flightless nature. The bones appear dark and fossilized, supported by discreet metal armatures for stability.

To the right, the visitor provides essential scale: an adult woman stands just behind the skeleton, her head level with the lower neck vertebrae, emphasizing that Gastornis towered over humans at approximately 1.8–2 meters (6–7 feet) tall. Her reaction – hands raised to her mouth in astonishment – adds a human element, evoking the universal sense of wonder these ancient giants inspire. The setting suggests a grand natural history museum hall, with high ceilings, a large arched window allowing daylight to illuminate the scene, and scattered fossil parts on the floor (possibly during setup or restoration). This composition not only showcases the fossil’s grandeur but immerses viewers in the prehistoric past, reminding us of a time when birds, not mammals, filled apex roles in ecosystems.

Tutorial tip: When analyzing museum photos like this, note how lighting and human scale enhance educational impact. The arched architecture and protective railing indicate a classic institution, likely emphasizing public engagement with fossils.

Step 2: Historical Context – Discovery and Classification of Gastornis

Trace the story of Gastornis like a detective tutorial, starting from its 19th-century discoveries. The genus was first described in 1855 by French paleontologist Gaston Planté, based on fossils from Paris Basin deposits in France, naming it after himself (Gastornis parisiensis). Early North American finds, such as those by Edward Drinker Cope in 1876 from New Mexico and Wyoming, were initially classified as Diatryma gigantea. For over a century, European and American specimens were treated separately due to minor differences, but modern analyses (including a 2024-2025 review resurrecting Diatryma for some species) confirm close relations, with many now synonymized under Gastornis.

Key milestones:

- 1916–1917: A nearly complete skeleton (AMNH 6169) from Wyoming’s Willwood Formation provided the first full view, mounted dramatically in museums.

- Ongoing debates: Recent studies, including a rediscovered skull of Diatryma geiselensis from Germany (misidentified for decades), have refined taxonomy, highlighting variations in skull structure.

These fossils date to the Paleocene–Eocene (about 56–45 million years ago), a warm period post-dinosaur extinction when birds rapidly diversified. Gastornis filled niches left by theropods, evolving in Europe and migrating to North America.

Tutorial exercise: Research taxonomic revisions using museum databases – names change as evidence accumulates, teaching the fluid nature of science.

Step 3: Physical Characteristics – Anatomy Breakdown

Dissect the skeleton as in a virtual anatomy lab, using the image as reference. Gastornis was a massive, ground-dwelling bird weighing up to 150–200 kg (330–440 lbs), with adaptations for a terrestrial lifestyle:

- Skull and Beak: The large, deep beak (visible prominently) was ideal for crushing – no sharp teeth or hooked tip like predators.

- Neck and Body: Long, flexible neck for reaching vegetation; robust ribcage and pelvis for supporting weight.

- Limbs: Powerful hind legs with short toes (no talons, as confirmed by footprints); tiny forelimbs, useless for flight but perhaps for balance.

- Overall Build: Bipedal stance with a horizontal back, similar to modern ostriches but bulkier.

The exhibit mount emphasizes its height and stability, with the tail possibly reconstructed for balance (original fossils lack complete tails). Scale comparison in the photo: The visitor’s shoulder aligns with the thigh, underscoring how Gastornis dwarfed early mammals like tiny horses (Hyracotherium).

Modern evidence (beak morphology, calcium isotopes in bones, blunted toes in footprints) supports a herbivorous diet – crushing seeds, nuts, or tough plants – overturning old “terror bird” predator myths (confused with South American phorusrhacids).

Tutorial tip: Compare to relatives like modern cassowaries (aggressive omnivores) or ostriches (herbivores) to understand convergent evolution in flightless birds.

Step 4: Scientific Facts and Insights – Paleobiology and Ecology

Advance to paleobiology in this tutorial section. Gastornis thrived in lush, subtropical forests of the Eocene Thermal Maximum, a greenhouse world with high CO₂ and no ice caps. As one of the largest land animals post-dinosaurs, it likely browsed high vegetation or foraged on the ground.

Key insights:

- Diet Debate Resolved: Early depictions as a horse-killing predator stemmed from size and beak power, but lack of claws, isotopic data showing plant-based nutrition, and biomechanical studies confirm herbivory.

- Locomotion: Not a fast runner (estimated 20–30 km/h); more of a deliberate walker in dense forests.

- Extinction: Vanished by mid-Eocene as climates cooled and mammal competitors rose.

- Evolutionary Links: Part of Gastornithiformes, close to waterfowl (Anseriformes) like ducksled ducks and geese – surprising for such a giant!

Fossil sites: Europe (France, Germany), North America (Wyoming, New Jersey), with rare Asian hints.

Tutorial exercise: Use online tools to model beak force – compare to parrots cracking nuts for analogy.

Step 5: Cultural and Educational Significance – Why This Exhibit Inspires Wonder

Conclude with the exhibit’s impact. Photos like this, capturing genuine reactions, highlight why Gastornis captivates: It challenges perceptions of birds as small/flying and showcases post-dinosaur recovery. Exhibits in institutions like the American Museum of Natural History or European counterparts educate on evolution, debunking myths (e.g., no more “Diatryma the killer”).

The human element – that moment of astonishment – mirrors public fascination, inspiring STEM careers. For educators: Use similar images for lessons on scale, adaptation, or scientific revision.

In summary, the Gastornis skeleton represents resilience and surprise in Earth’s history. This guide, inspired by the image’s evocative scene, equips you to appreciate its majesty fully. Visit a natural history museum to experience it firsthand – the awe is contagious! For further reading, explore peer-reviewed sources on Gastornithiformes or virtual fossil tours.