Majungasaurus Crenatissimus Exhibit: A Comprehensive Tutorial on Theropod Anatomy, Cannibalistic Behavior, and Museum Reconstruction

Introduction to Majungasaurus Crenatissimus

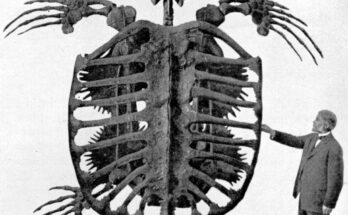

The image illustrates a dramatic museum exhibit featuring the mounted skeleton of Majungasaurus crenatissimus, a Late Cretaceous abelisaurid theropod from Madagascar, depicted in a predatory pose over the disarticulated remains of a Rapetosaurus krausei, a titanosaur sauropod. Housed in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, this display captures a moment of feeding, with the Majungasaurus rearing on its hind legs, jaws agape, forelimbs extended, and tail curving around the scattered vertebrae and skull of its prey on a sandy base. Living around 70-66 million years ago in the Maevarano Formation, Majungasaurus measured about 6-7 meters (20-23 feet) in length and weighed up to 1,100 kilograms (2,425 pounds), making it the apex predator of its island ecosystem. This tutorial-style guide dissects the exhibit step by step, covering identification, skeletal anatomy, historical discoveries, behavioral ecology, and interpretive significance. Suited for paleontologists, students, or museum visitors, it provides a professional framework for analyzing such dynamic displays, enhancing your understanding of Cretaceous carnivores.

Begin with the overall composition: The theropod’s bipedal stance emphasizes its balance on powerful hind limbs, with the neck arched forward in attack mode. Scattered bones on the ground, including the elongated sauropod neck and skull, evoke a fresh kill, while background elements like glass railings and other exhibits (e.g., a suspended marine reptile skeleton) situate it in a modern museum hall. This reconstruction highlights Majungasaurus’ role as a versatile hunter in floodplain environments teeming with rivers and vegetation.

Step 1: Identifying the Skeleton and Pose – Key Diagnostic Traits

Start your analysis as in a field identification tutorial: Recognize Majungasaurus by its robust, short-snouted skull with a rough, rugose texture and small horn-like projection above the eye, distinguishing it from tyrannosaurids like T. rex (which has a more massive build) or allosaurids (with longer snouts). In the image, the skull measures about 60-70 cm (2-2.3 feet) long, featuring sharp, serrated teeth up to 8 cm (3 inches) for tearing flesh. The reduced forelimbs, with only two functional digits, are characteristic of abelisaurids, adapted for grasping rather than primary hunting.

Examine the pose: Curated to depict predation, the skeleton rears at a 45-degree angle, supported by a hidden armature, with the tail providing counterbalance via its 30+ caudal vertebrae. The prey remains—Rapetosaurus’ cervical vertebrae and skull—illustrate trophic interactions, based on fossil evidence of bite marks on sauropod bones. For museum verification, note ROM’s label (not visible here) often includes details on the specimen’s provenance from Madagascar’s Mahajanga Basin.

Step 2: Anatomical Breakdown – Exploring Skeletal Adaptations

Dissect the anatomy like a comparative osteology tutorial: Focus first on the axial skeleton. The vertebral column, with 10 cervical, 13 dorsal, 5 sacral, and 35-40 caudal vertebrae, supports a semi-rigid body for stability during charges. In the exhibit, the S-curved neck and tail demonstrate flexibility for quick turns, while the ribcage protects a large digestive system suited for opportunistic feeding.

Shift to appendages: Hind limbs are pillar-like, with a femur up to 80 cm (2.6 feet) long, enabling speeds of 20-30 km/h (12-19 mph) in short bursts. The tiny arms, about 25 cm (10 inches) long, end in clawed hands possibly used for holding prey. The pelvis, broad and fused, anchors strong leg muscles. Preparation techniques involve CT scanning originals to create casts, as many exhibits use replicas to preserve fragile fossils. Compare to relatives like Carnotaurus, noting Majungasaurus’ more pronounced cranial ornamentation for display.

Step 3: Historical Discoveries and Fossil Record – Unearthing the Evidence

Trace the paleontological history: Majungasaurus was first described in 1896 by Charles Depéret as Megalosaurus crenatissimus, later reclassified in 1979 by Philippe Taquet. Key expeditions in the 1990s by Stony Brook University and the University of Antananarivo unearthed nearly complete skeletons, including FMNH PR 2100, revealing brain structure via endocasts. Fossils from the Maevarano Formation show pathologies like infections and bite marks, confirming cannibalism—unique evidence where tooth marks match the species’ dentition.

Excavation methods include plaster jacketing for transport, with ROM’s mount incorporating casts from multiple specimens to depict behavior inferred from 2007 studies. Growth studies indicate a lifespan of 20-30 years, with rapid juvenile growth.

Step 4: Behavioral and Ecological Insights – Reconstructing Predatory Life

Rebuild the paleoecology: As an insular predator on ancient Madagascar, Majungasaurus hunted in semi-arid floodplains, preying on sauropods like Rapetosaurus and possibly smaller theropods. Cannibalism, evidenced by gnawed bones, likely occurred during droughts or resource scarcity, with teeth replaced every 56 days to maintain sharpness. Behaviorally, it may have ambushed prey using stealth, with a keen sense of smell inferred from large olfactory lobes.

The exhibit’s predation scene draws from bite mark analyses, portraying a solitary hunter rather than pack behavior. Extinction aligned with the K-Pg event, though isolated on Madagascar.

Step 5: Museum Interpretation and Modern Relevance – Educational Impact

Exhibits like ROM’s, opened in the early 2000s, use dynamic poses to engage visitors, incorporating lighting and dioramas for immersion. For analysis, consider reconstructions: Horns may have been keratin-covered, and colors inferred from melanosomes in related species. Modern studies employ finite element analysis to model bite forces around 8,000-15,000 Newtons.

This display educates on island biogeography and evolution, paralleling current conservation of isolated ecosystems. Tips for visitors: Use audio guides for deeper insights into cannibalism evidence.

In conclusion, the Majungasaurus exhibit vividly revives Cretaceous drama, offering profound lessons in theropod biology. Apply this guide to enrich your museum explorations or research.