The Fighting Dinosaurs: Velociraptor mongoliensis vs. Protoceratops andrewsi – A Comprehensive Tutorial on Discovery, Morphology, Behavioral Insights, and Preservation of an Iconic Fossil Specimen

Paleontology often uncovers snapshots of ancient life frozen in time, but few are as dramatic and evocative as the “Fighting Dinosaurs” specimen—a rare fossil capturing a Velociraptor mongoliensis and a Protoceratops andrewsi seemingly locked in mortal combat. Discovered in the windswept sands of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, this Late Cretaceous artifact (dated 75–71 million years ago) provides direct evidence of predator-prey interactions, challenging our perceptions of dinosaur behavior and ecology. Now housed as a national treasure in Mongolia, the specimen has inspired decades of research, museum exhibits, and popular culture depictions, including influences on films like Jurassic Park. This tutorial-style article guides you through a systematic exploration of the Fighting Dinosaurs, emulating the paleontological process from fieldwork to interpretation. We’ll proceed step by step: establishing provenance and discovery, tracing historical classifications and displays, dissecting morphology via visual and documented analysis, evaluating scientific implications, and addressing ongoing debates. Insights are synthesized from primary sources, institutional records, and peer-reviewed studies up to September 2025, empowering students, researchers, and enthusiasts to critically analyze this extraordinary find.

Step 1: Establishing Provenance and the History of Discovery

Begin with the foundational step of any fossil analysis: verifying where, when, and how the specimen was found, as this anchors all subsequent interpretations in geological and environmental context. The Fighting Dinosaurs were unearthed on August 3, 1971, during a joint Polish-Mongolian paleontological expedition in the Gobi Desert, specifically at the Tugriken Shire (also spelled Tugrugyin Shireh) locality within the Djadokhta Formation’s Turgrugyin Member. This formation, part of the Barun Goyot basin, consists of red-orange sandstones deposited in arid, dune-dominated environments during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous (approximately 75–71 million years ago), based on magnetostratigraphy and faunal correlations. The expedition, spanning 1963–1971, targeted vertebrate fossils in the Djadokhta and Nemegt formations, yielding over 30 significant specimens.

The discovery team, including Polish paleontologists Tomasz Jerzykiewicz, Maciej Kuczyński, Teresa Maryańska, Edward Miranowski, and Mongolian collaborators Altangerel Perle and Wojciech Skarżyński, spotted overlapping skull fragments protruding from the sediment, prompting excavation. The block, measuring about 2 meters across, was jacketed in plaster for transport and nicknamed the “Fighting Dinosaurs” due to its combative pose. Cataloged as MPC-D 100/512 (Protoceratops) and MPC-D 100/25 (Velociraptor) at the Mongolian Paleontological Center (formerly GIN or GI SPS), the original remains a Mongolian national treasure, with casts distributed worldwide for study and display. As of 2025, the original is housed at the Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, following repatriation efforts and institutional reorganizations. To replicate this in your research, consult field logs (e.g., via the Paleobiology Database) and stratigraphic maps to reconstruct paleoecosystems—here, a semi-arid desert with episodic sandstorms, home to small dinosaurs adapted to harsh conditions.

Step 2: Historical Classification, Exhibits, and Cultural Impact

Next, chart the specimen’s taxonomic and exhibition history to understand evolving scientific narratives. The Velociraptor mongoliensis, first described by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1924 from earlier Gobi finds, is a small dromaeosaurid theropod (about 2 meters long, 15–20 kg), while Protoceratops andrewsi, named by Walter Granger and W.K. Gregory in 1923, is a basal ceratopsian (1.5–2 meters long, 80–180 kg). Initial descriptions in the 1970s by Rinchen Barsbold and others classified the interaction as predatory, solidifying their species identities without controversy.

The specimen gained global fame through exhibitions, notably the American Museum of Natural History’s (AMNH) “Fighting Dinosaurs: New Discoveries from Mongolia” in 2000, which featured a cast and highlighted over 30 Gobi fossils, drawing crowds to witness the “action pose” preserved 80 million years ago. Casts have since appeared in museums like the Natural History Museum in London and various traveling shows, influencing media—Velociraptor’s sickle claw tactics inspired Jurassic Park raptors. In Mongolia, it’s leveraged for tourism, with events at sites like Bayanzag in 2023 promoting dinosaur heritage. For your studies, trace classifications using tools like the Paleobiology Database, noting how behavioral inferences (e.g., active predation) have refined theropod ecology models.

Step 3: Detailed Morphological Description and Analysis

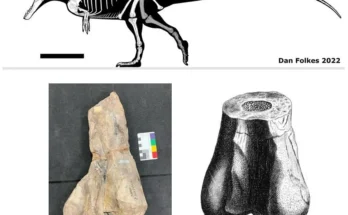

With context set, conduct a virtual osteological examination, as if preparing the specimen in a lab. The fossil block, embedded in sandstone matrix, captures both dinosaurs in ventral view, with the Protoceratops beneath and the Velociraptor atop, suggesting a mid-struggle burial. The specimen is largely complete but shows taphonomic alterations, such as missing limbs on the Protoceratops, likely from post-mortem scavenging.

- Protoceratops andrewsi Morphology: In semi-erect posture with a horizontal skull, this quadrupedal herbivore features a parrot-like beak, frilled neck shield, and robust jaws clamped on the Velociraptor’s right arm, fracturing it. Anomalies include a broken pectoral girdle (small bone fragments in coracoids) and displaced right forelimb/scapulocoracoid, twisted backward—evidence of forceful trauma. Body length ~1.8 meters; preserved elements include skull, vertebrae, ribs, and partial limbs.

- Velociraptor mongoliensis Morphology: Positioned prone, this bipedal carnivore has its left hand gripping the Protoceratops’ frill (scratching the skull), right hand trapped in the jaws, and sickle-clawed feet embedded in the throat (near carotid arteries) and abdomen. Key features: elongated snout with serrated teeth, feathered-like arm structures (inferred from relatives), and raptorial claws for slashing. More complete than its opponent, with intact tail and hindlimbs; length ~2 meters.

Bone surfaces show vascular traces and minimal distortion, indicating rapid burial. For analysis, use digital photogrammetry on images to measure angles (e.g., claw penetration ~45 degrees) and compare to CT scans in studies like those by Unwin et al. (1995).

Step 4: Scientific Significance and Behavioral Insights

Synthesize the specimen’s contributions to paleobiology, emphasizing its role in evidencing dinosaur interactions. As one of the few fossils showing direct agonism, it demonstrates Velociraptor’s hunting strategy: ambush with sickle claws targeting vital areas, supporting active predation over scavenging. For Protoceratops, it reveals defensive capabilities, using jaws to counterattack despite being herbivorous. Ecologically, it highlights Djadokhta’s food web, with small theropods preying on ceratopsians in a resource-scarce desert. Histological and isotopic studies (e.g., on claw marks) could further age the individuals—Velociraptor likely adult, Protoceratops subadult. To apply this, integrate with biomechanical models (e.g., via software like ANSYS) to simulate bite forces (~1,000 N for Velociraptor).

Step 5: Addressing Debates, Interpretations, and Future Research

Conclude with critical evaluation, as debates refine science. Hypotheses for preservation include quicksand entrapment (Barsbold, 1974), dune collapse during scavenging (Osmólska, 1993), sandstorm burial mid-fight (Unwin et al., 1995), or mutual death from wounds followed by scavenging (Carpenter, 1998). Barsbold (2016) suggested herd intervention dislocating limbs. No major taxonomic controversies exist, but behavioral ones persist—was it predation, defense, or coincidence? As of 2025, advanced imaging (e.g., synchrotron scans) could resolve soft tissue traces, while Mongolian tourism initiatives may fund further excavations.

This tutorial illustrates how a single fossil like the Fighting Dinosaurs can illuminate ancient dramas. Visit casts at institutions like AMNH or the original in Mongolia to experience it—what do you interpret from the pose? Engage in the comments!