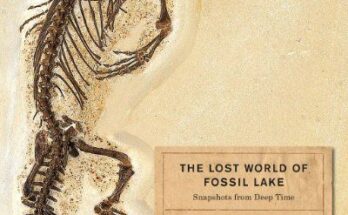

Prehistoric Megafauna: Artistic Reconstructions, Fossils, and Behavioral Insights into Extinct Giants

Introduction to the Collage: A Visual Journey Through Prehistory

In this detailed exploration, we delve into a captivating collage that brings to life some of Earth’s most enigmatic extinct creatures from the Pleistocene epoch. This image compilation serves as a bridge between artistic imagination, paleontological evidence, and the dramatic behaviors of ancient megafauna. Composed of three distinct panels, the collage features a digital reconstruction of a unicorn-like rhinoceros, a real fossilized skull from the same species, and a dynamic scene of two massive, tusked beasts engaged in combat. Whether you’re a student of paleontology, an artist inspired by ancient life, or simply a curious enthusiast, this post will guide you through each element step by step, providing professional insights, historical context, and scientific details to enhance your understanding. Think of this as a tutorial on appreciating paleoart and fossils— we’ll break it down systematically, explaining how such visuals are created, interpreted, and what they reveal about our planet’s past.

By the end of this article, you’ll not only have a comprehensive description of the image but also practical knowledge on how paleontologists reconstruct extinct animals, the significance of fossil evidence, and the ecological roles these creatures played. We’ll use the collage as our central exhibit, referencing each section to build a layered narrative. Let’s begin with an overview of the collage’s composition before diving into each panel.

The overall image is arranged in a triptych format: the top row splits into two side-by-side panels (left: artistic reconstruction; right: museum-displayed fossil), while the bottom occupies the full width with a panoramic action scene. The color palette evokes a sense of antiquity—muted grays and blues for the top panels contrast with the warm, dusty oranges of the bottom, symbolizing the shift from static evidence to lively behavioral reconstruction. This layout is common in educational paleoart, where artists and scientists collaborate to make ancient worlds accessible. Now, let’s examine each component in detail, starting from the top left.

Panel 1: Artistic Reconstruction of Elasmotherium – The Siberian Unicorn

The top-left panel presents a highly detailed digital illustration of Elasmotherium sibiricum, often dubbed the “Siberian Unicorn” due to its legendary single horn. This prehistoric rhinoceros, which roamed the Eurasian steppes during the Late Pleistocene (approximately 39,000 to 29,000 years ago), is depicted in a close-up profile view against a subtle greenish-gray background. The creature’s head dominates the frame, showcasing a massive, elongated horn protruding from its forehead. Unlike the smooth horns of modern rhinoceroses, this one is rendered with a serrated, ridged texture along its length, suggesting a keratinous structure adapted for defense or foraging—though actual horn fossils are rare, as they decompose easily.

To appreciate this reconstruction like a paleoartist would, consider the step-by-step process behind it:

- Research Fossil Evidence: Paleontologists base such images on skeletal remains. Elasmotherium fossils, first described in the 19th century by Russian scientists, indicate an animal up to 4.5 meters long and weighing over 4 tons—larger than today’s white rhino. The skull’s prominent nasal boss (a bony protuberance) supports the idea of a single, enormous horn, potentially up to 2 meters long.

- Anatomical Accuracy: The artist has faithfully rendered the beast’s robust, barrel-shaped head with thick, wrinkled skin resembling that of modern Indian rhinoceroses. Small, beady eyes peer forward with a vigilant expression, while short, rounded ears and a wide, prehensile upper lip hint at its grazing habits. The fur is depicted as short and coarse, adapted for cold climates, drawing from comparisons to woolly rhinoceros relatives.

- Artistic Choices for Realism: Lighting and shading add depth—the horn casts a subtle shadow on the face, emphasizing its curvature and texture. The muted background keeps focus on the subject, a technique used in scientific illustrations to isolate features for study. If you’re creating similar art, tools like Adobe Photoshop or Blender can simulate these effects; start with a 3D model based on scanned fossils, then layer textures from modern analogs.

- Scientific and Cultural Context: This depiction ties into mythology. Marco Polo’s accounts of unicorns may stem from Elasmotherium fossils traded along the Silk Road. Extinction factors include climate change and human hunting, with the last individuals surviving until around 39,000 years ago, overlapping with early Homo sapiens.

This panel exemplifies how paleoart educates: it transforms dry bones into a living entity, sparking interest in conservation parallels for modern endangered rhinos.

Panel 2: Fossilized Skull of Elasmotherium – A Window into the Past

Adjacent to the reconstruction, the top-right panel shifts to tangible evidence: a photograph of an actual Elasmotherium skull on display in a museum setting. Captured in a well-lit glass case, the skull is angled slightly upward, highlighting its massive, conical nasal horn base made of fossilized bone. The off-white, weathered surface shows natural cracks and textures from millennia underground, with empty eye sockets and a broad jawline underscoring the animal’s herbivorous diet—wide molars for grinding tough grasses.

Here’s a tutorial-style breakdown on interpreting and studying such fossils:

- Identification and Provenance: This skull likely hails from Siberian or Kazakhstani sites, where permafrost preserves remains exceptionally well. Key features include the fused nasal bones forming the horn boss, distinguishing it from bicorn rhinos like Diceros. Measure it: skulls can span over 1 meter, with the horn base alone suggesting immense leverage for rooting or combat.

- Preparation and Display Techniques: Museums prepare fossils by excavating, cleaning with brushes and chemicals, and mounting on stands. The background here includes blurred exhibit elements (e.g., informational plaques), typical of institutions like the Natural History Museum in London or Moscow’s Paleontological Institute. If replicating for educational purposes, use 3D printing from CT scans to create replicas.

- Paleobiological Insights: Analyze wear patterns—teeth erosion indicates a diet of abrasive vegetation. The skull’s robust structure implies head-butting behaviors, similar to modern rams. Isotopic analysis of bones reveals migration patterns across Ice Age tundras.

- Conservation Lessons: Fossils like this remind us of biodiversity loss. Elasmotherium’s extinction correlates with the Quaternary extinction event, driven by glacial shifts and megafauna overhunting. Today, efforts like de-extinction via genetic engineering (e.g., using elephant DNA for mammoths) draw inspiration from such relics.

Juxtaposing this with the reconstruction teaches a core lesson in paleontology: fossils provide the blueprint, while art fills in the gaps.

Panel 3: Dramatic Clash of Woolly Mammoths – Behavioral Reconstruction in Action

The bottom panel expands into a full-width, cinematic artwork depicting two woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) locked in combat amid a savanna-like landscape at sunset. Dust swirls around their massive forms as curved tusks interlock, trunks raised in aggression, and muscular bodies strain forward. The scene is bathed in golden hues, with sparse acacia trees and a hazy horizon evoking the Pleistocene African or Eurasian plains. Fur coats—long, shaggy, and reddish-brown—ripple with movement, capturing the intensity of a territorial dispute or mating rivalry.

Approach this as a tutorial on reconstructing animal behavior from fossils:

- Basis in Evidence: Woolly mammoths, extinct around 4,000 years ago (with isolated populations on Wrangel Island), are known from frozen carcasses in Siberia, preserving skin, fur, and even stomach contents. Tusks, up to 4 meters long, show scars from clashes, confirmed by skeletal trauma studies.

- Artistic Composition Steps: Artists like Mark Hallett (noted in the signature “M. Hatt”) start with sketches from fossils. Layer digital paints for depth: foreground dust uses particle effects, while backlighting creates dramatic silhouettes. For your own creations, reference videos of modern elephants fighting to animate poses realistically.

- Behavioral Ecology: This scene illustrates musth-driven combats in males, where hormones surge for dominance. Mammoths lived in herds, migrating across tundras, feeding on grasses. Climate warming and human spears contributed to their demise, with cave art (e.g., Lascaux) depicting similar hunts.

- Educational Applications: Such art is used in documentaries (e.g., BBC’s “Walking with Beasts”) to visualize extinct ecosystems. It highlights human impact—today’s African elephants face similar threats from poaching.

This panel ties the collage together, moving from static portraits to dynamic life, emphasizing the tragedy of extinction.

Conclusion: Lessons from the Collage for Modern Audiences

This collage isn’t just visually stunning; it’s a tutorial in paleontology, blending art, science, and history to resurrect lost worlds. From Elasmotherium’s mythical horn to the mammoths’ epic battles, it underscores the fragility of life amid environmental change. For website visitors, use this as inspiration: explore museums, read journals like Palaeontology, or create your own reconstructions using free tools like GIMP. By understanding these giants, we better protect today’s biodiversity. If this sparks your interest, consider diving deeper into related topics like the La Brea Tar Pits or cloning ethics.

This post, based on the provided image, aims to provide a professional, exhaustive resource—perfect for educators, artists, or anyone fascinated by prehistory. Share your thoughts in the comments!