Dimetrodon: The Sail-Backed Synapsid Predator of the Permian – Exploring a Classic Vintage Paleoart Illustration

Description:

The image is a captivating page from a mid-20th-century children’s book on prehistoric life, featuring a vivid, classic illustration of Dimetrodon—an iconic sail-backed creature dramatically posed in a Permian landscape. The text describes its “wings of a bat and a long dorsal fin” (reflecting outdated ideas of the sail as fin-like), heterodont dentition (“teeth in two sizes”), probable size (over 3 meters/10 feet and 300 kg/660 lbs), and sail function (thermoregulation and possible display). This tutorial-style guide examines the artwork step-by-step, contrasting historical depictions with modern scientific understanding. Ideal for educators, paleoart enthusiasts, students, and collectors, we’ll cover identification, anatomy, evolutionary significance, outdated vs. current views, and famous fossils—providing a professional, in-depth resource on this mammal ancestor often mistaken for a dinosaur.

Step 1: Analyzing the Vintage Illustration – Historical Context and Artistic Style

This illustration exemplifies mid-century paleoart, likely from the 1940s–1960s era of books like those influenced by Charles R. Knight or similar artists. Dimetrodon is depicted in a dynamic, aggressive pose: crouched low with mouth open, revealing sharp teeth, and its massive sail prominently displayed against a sparse, arid background with early plants. The scaly, reptilian skin and sprawling limbs reflect the era’s view of synapsids as “mammal-like reptiles.”

The accompanying text mixes accurate observations (heterodont teeth, carnivory) with outdated ideas: comparing the sail to bat wings or a dorsal fin, and suggesting it as a “prototype” linking to monstrous forms. Such books popularized Dimetrodon but perpetuated misconceptions, like classifying it near dinosaurs.

A similar classic vintage Dimetrodon illustration from an old prehistoric life book:

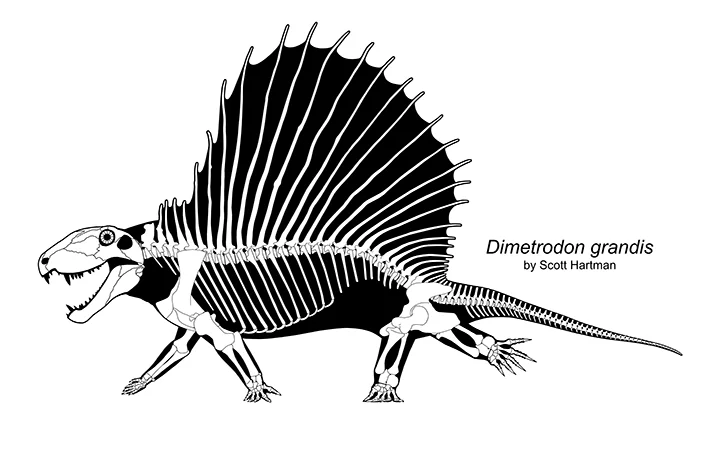

Step 2: Correcting the Misconceptions – Dimetrodon Is Not a Dinosaur

Dimetrodon is a synapsid (mammal lineage precursor), not a reptile or dinosaur. It lived during the Early Permian (295–272 million years ago), ~40 million years before the first dinosaurs. Belonging to Sphenacodontidae, it is more closely related to mammals than to lizards or dinosaurs—sharing traits like differentiated teeth and possibly glandular skin.

The name “Dimetrodon” means “two measures of teeth,” referring to heterodonty: sharp incisors/canines for piercing and smaller shearing teeth for slicing flesh—advanced for its time and convergent with mammals.

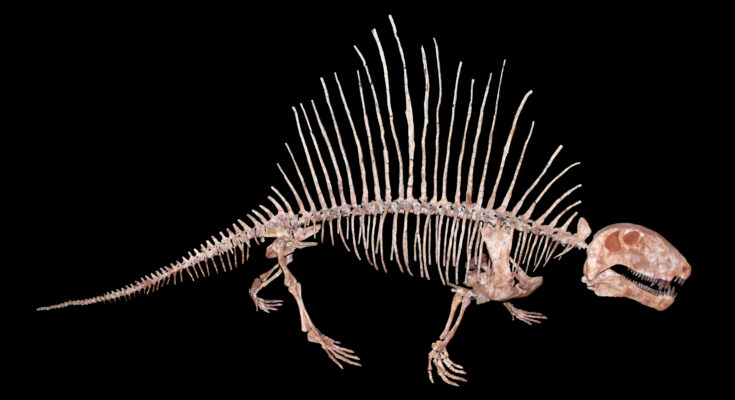

Step 3: Anatomy of Dimetrodon – The Sail and Specialized Features

The most striking feature is the neural spine sail: elongated vertebral spines (up to 1 meter tall in large species) connected by skin, richly vascularized. Modern consensus: primarily for thermoregulation—absorbing heat quickly in the morning (a 200 kg individual could warm from 26°C to 32°C in ~80 minutes with sail vs. 205 without) and dissipating excess via blood flow. Secondary roles: display (intimidation/mating) or species recognition.

- Size: 1.7–4.6 meters long, 28–250 kg (larger species like D. grandis up to 4.6 m and heavier).

- Dentition: Ziphodont (serrated, teardrop-shaped in cross-section) for efficient meat-slicing.

- Posture: More upright than sprawling, with powerful limbs for terrestrial hunting.

- Recent discoveries (e.g., 2025 scaly impressions from Germany) confirm scaled skin, though the sail’s webbing may not reach spine tips (crooked spines suggest partial coverage).

Modern scientific reconstruction contrasting vintage views:

Step 4: Paleobiology and Ecology – Apex Predator of the Permian

As a top carnivore in lowland floodplains (e.g., Texas Red Beds, resembling modern Everglades but arid), Dimetrodon hunted amphibians (like Diplocaulus—direct evidence from bite marks), reptiles, and smaller synapsids. Fully terrestrial, it preyed on herbivores like Edaphosaurus (which had a similar but cross-barred sail, evolved independently).

The sail’s evolution: gradual from low crests in ancestors; thermoregulation likely secondary, with display primary early on.

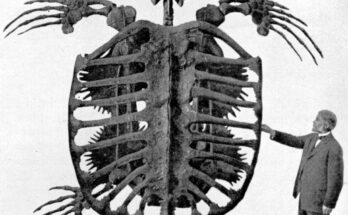

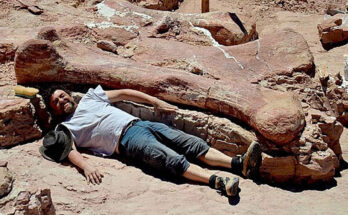

Fossil evidence of predation and environment:

Step 5: Fossil Record and Famous Specimens

Best fossils from Texas/Oklahoma Red Beds and German Bromacker site. Iconic mounts at AMNH (New York), Field Museum (Chicago), and others feature complete skeletons showing sail spines.

Tutorial tip: Compare vintage art (lizard-like, sprawling) to modern (agile, mammal-precursor traits). Artists like Charles R. Knight popularized the “reptilian” look in the early 1900s.

Another classic by Charles R. Knight or similar era:

Step 6: Cultural Legacy and Modern Relevance

Dimetrodon’s popularity stems from toy sets and books misgrouping it with dinosaurs. Today, it illustrates synapsid evolution toward mammals—highlighting traits like heterodonty and potential endothermy precursors.

For further study: Visit museums with Dimetrodon mounts or explore 3D models online. Ethical note: Appreciate vintage art for its historical value while embracing updated science.

In summary, this charming vintage page captures Dimetrodon’s enduring fascination—a sail-backed bridge to mammal origins. From outdated “fin” theories to thermoregulatory marvels, it invites us to trace paleoart’s evolution alongside the creatures it depicts.