Islands of Evolution: Shell Variation in Galápagos Giant Tortoises – A Museum Exhibit Tutorial at the California Academy of Sciences

Description:

The captivating image showcases the renowned “Islands of Evolution” exhibit at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, a permanent installation highlighting adaptive radiation and natural selection through iconic specimens from the Galápagos Islands and Madagascar. At the center is a large wall display titled “THE GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS,” featuring a detailed map of the archipelago and five suspended giant tortoise shells demonstrating morphological variation. Below, a glass case holds an additional specimen, with a sign reading “ISLANDS OF EVOLUTION” accompanied by a world map illustrating global island biodiversity hotspots. This professional tutorial-style guide breaks down the exhibit step-by-step, ideal for educators, students, researchers, and visitors. We’ll explore the biology of Galápagos giant tortoises (Chelonoidis complex), shell adaptations, historical context including Charles Darwin’s observations and the Academy’s 1905–1906 expedition, and modern conservation implications.

Step 1: Overview of the Exhibit – Contextualizing the Display

The “Islands of Evolution” exhibit, designed to immerse visitors in the processes of speciation on isolated islands, uses real and replica specimens to illustrate how geographic isolation drives evolutionary change. The Galápagos section focuses on giant tortoises as a prime example of adaptive radiation—the diversification of a single ancestor into multiple forms suited to different environments.

In the image, five tortoise carapaces (upper shells) hang from the ceiling, connected by red lines to specific islands on the map behind them. This visual aid demonstrates how shell shape correlates with habitat: domed shells for moist highlands and saddleback shells for arid lowlands. The lower glass case likely contains a full mounted specimen or additional shell for close inspection. The exhibit draws from the Academy’s historic collections, including tortoises gathered during its landmark 1905–1906 Galápagos expedition, which brought back thousands of specimens after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake nearly destroyed the institution.

For a similar view of the exhibit’s immersive design:

Step 2: Anatomy of Galápagos Tortoise Shells – Domed vs. Saddleback Forms

Galápagos giant tortoises exhibit remarkable intraspecific variation in carapace morphology, with a continuum between two extremes:

- Domed shells: Rounded, convex, and voluminous, found on larger tortoises from humid, high-elevation islands (e.g., Santa Cruz, Alcedo Volcano on Isabela). These allow for greater body mass (up to 400 kg/880 lbs in males) and shorter necks, ideal for grazing low-lying grasses and herbs in lush vegetation.

- Saddleback shells: Flatter with an upward-arching frontal edge (resembling a Spanish saddle, hence “galápago”), enabling longer necks to extend upward for browsing taller cacti and shrubs. These occur on smaller tortoises from drier, low-elevation islands (e.g., Española, Pinzón), where food is scarcer and higher off the ground.

Intermediate forms exist, such as on some Isabela populations. The five hanging shells in the image likely represent this spectrum, progressing from extreme saddleback (far left) to fully domed (far right), tied to islands with varying aridity and vegetation height.

Tutorial tip: Shell shape influences self-righting ability—if flipped, domed tortoises use shorter limbs more efficiently, while saddlebacks may struggle but gain feeding advantages. Genetic studies confirm these traits evolved multiple times, driven by natural selection.

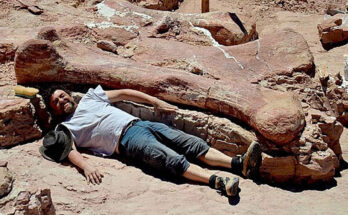

Close-up examples of domed and saddleback shell variations:

Step 3: Evolutionary Significance – Darwin’s Observations and Adaptive Radiation

Charles Darwin, during the HMS Beagle voyage in 1835, noted shell differences among islands. The vice-governor of the Galápagos reportedly could identify a tortoise’s origin by its shell alone—a key anecdote sparking Darwin’s ideas on natural selection.

Tortoises descended from a small South American ancestor that rafted to the islands ~2–3 million years ago. Isolation on volcanic islands with diverse microclimates led to 15 recognized taxa (12 extant), each adapted to local conditions. This radiation mirrors finches and mockingbirds, making the Galápagos a “living laboratory” of evolution.

The exhibit’s map ties shells to islands, illustrating biogeography: saddlebacks on arid Española/Pinzón, domed on wetter Santa Cruz/Isabela.

Step 4: Historical Collections and the California Academy’s Role

The Academy’s 1905–1906 expedition, led by Rollo Beck, collected critical specimens—including the holotype of the Fernandina tortoise (C. phantasticus), long thought extinct until a 2019 rediscovery. These shells, many still in the collection, inform the exhibit and ongoing research (e.g., DNA from historic bones revealing lost lineages).

Post-expedition, whaling and invasive species reduced populations from ~250,000 to ~15,000 by the 1970s. Captive breeding and repatriation have boosted numbers to ~20,000–30,000 today.

Step 5: Modern Conservation and Exhibit Interpretation

The “Islands of Evolution” sign with a world map compares Galápagos to Madagascar, emphasizing island endemism vulnerability. Threats like goats (removed via Project Isabela) and climate change persist, but successes include restoring Española tortoises from 15 individuals to thousands.

Tutorial application: When visiting, trace red lines from shells to islands on the map. Note how elevation and rainfall drive adaptation—arid lowlands favor saddlebacks for reaching Opuntia cacti.

Another view of tortoise shell diversity in museum contexts:

In summary, this exhibit masterfully uses Galápagos tortoise shells to teach evolution by natural selection—variation, inheritance, and differential survival in isolated habitats. From Darwin’s insights to the Academy’s historic specimens, it bridges past discoveries with urgent conservation, inspiring awe for these gentle giants that named the islands themselves.