Xiphactinus audax: The Ferocious Bulldog Fish of the Cretaceous Seas – A Detailed Paleontological Tutorial from Museum Exhibits

Description:

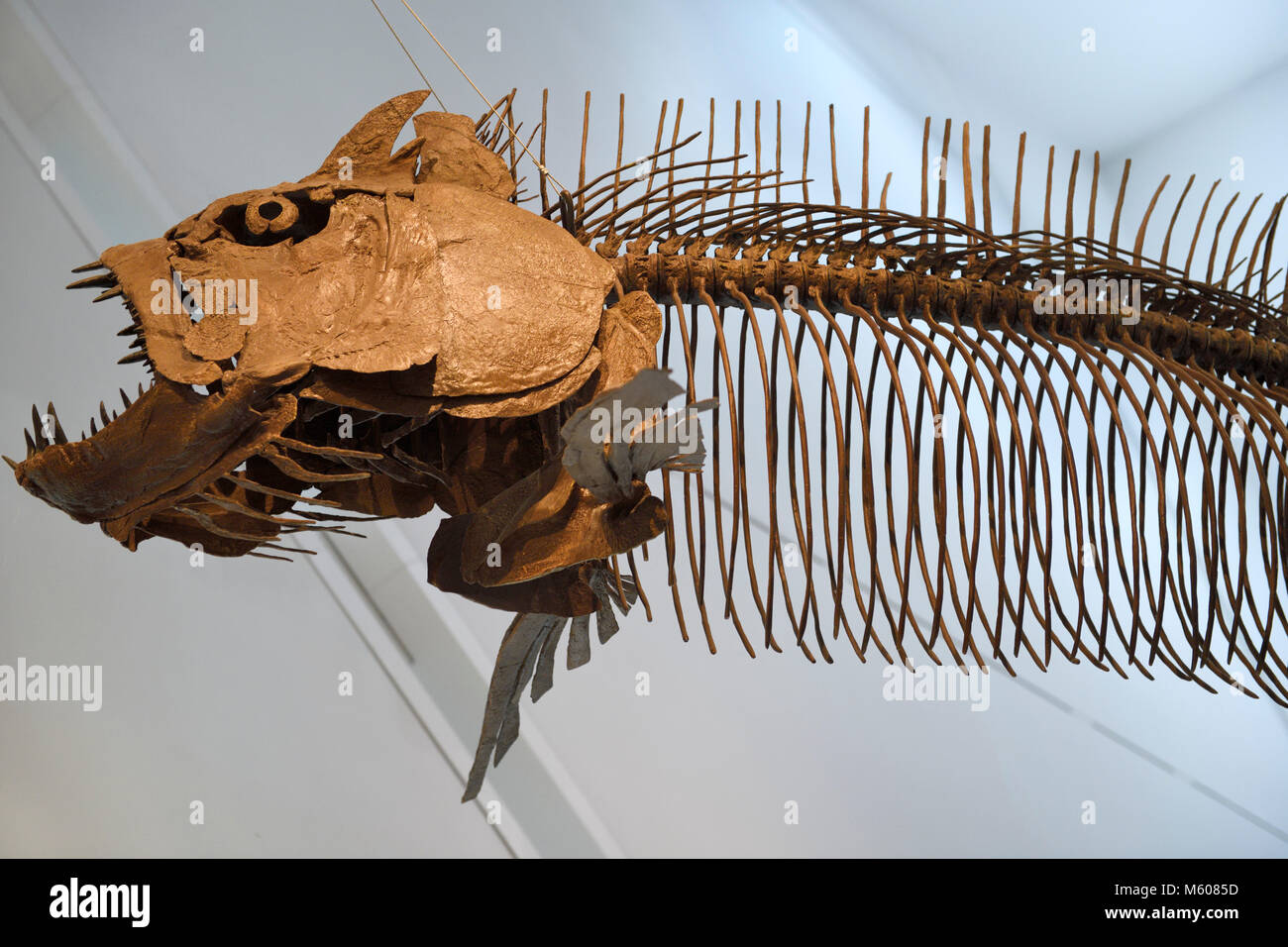

The striking image captures a dramatic museum exhibit: a massive, suspended skeleton of Xiphactinus audax, one of the largest and most fearsome predatory bony fish of the Late Cretaceous period (approximately 87 to 82 million years ago). Hung from the ceiling in a dynamic diving pose, the skeleton highlights its elongated body, powerful pectoral fins, extensive rib cage, and a massive skull armed with long, fang-like teeth—evoking a “bulldog” appearance with an upturned jaw. This professional tutorial-style guide explores the species step-by-step, ideal for educators, students, researchers, and enthusiasts. Drawing on the exhibit’s details and iconic fossils, we’ll cover identification, anatomy, paleobiology, famous specimens, and notable museum displays to provide an in-depth resource for understanding this apex predator of the Western Interior Seaway.

Step 1: Identifying the Specimen in the Image – Overview of Xiphactinus audax

The skeleton belongs to Xiphactinus audax (meaning “bold sword-ray” from Greek and Latin), an extinct genus of large ichthyodectid teleost fish. Adults reached lengths of 4.5 to 6 meters (15 to 20 feet), making it one of the largest bony fish of its time—comparable in size to a modern great white shark but with a more streamlined, tarpon-like body. The exhibit’s diving posture emphasizes its role as a fast-swimming ambush predator in the open waters of the Western Interior Seaway, an immense inland ocean that bisected North America during the Cretaceous.

Key visual traits in the image include the robust skull (about 60–90 cm long in large adults), protruding conical fangs up to 5 cm, and a long, flexible body supported by numerous vertebrae and rib-like structures for hydrodynamic efficiency. Such hanging mounts are common in museums to convey the fish’s agility and scale in three dimensions.

A similar dramatic hanging skeleton display in a museum setting:

Step 2: Anatomy of Xiphactinus – Breaking Down the Skeleton

Study the skeleton like a paleontologist: Start with the skull, featuring a short, deep muzzle, large orbits for keen vision, and irregular, glistening fangs for grasping slippery prey. The jaw’s upward tilt and powerful musculature allowed a wide gape to engulf large victims whole.

The body is sleek and muscular, with large pectoral fins (wing-like for maneuvering) and a strong caudal fin for propulsion—estimates suggest bursts of speed up to 40–60 km/h (25–37 mph). The extensive dorsal and ventral fin rays (visible as spines along the back) provided stability, while the rib cage protected vital organs in high-speed pursuits.

Tutorial tip: Compare to modern analogs—Xiphactinus resembled a giant, fanged tarpon but was unrelated, converging on similar predatory adaptations. Fossils from the Niobrara Chalk (Kansas) preserve fine details due to anoxic bottom conditions that minimized scavenging.

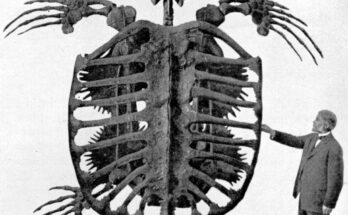

Close-up of a comparable Xiphactinus skull and full skeleton:

Step 3: Paleobiology and Behavior – A Voracious Apex Predator

Xiphactinus was a top predator in the Western Interior Seaway, hunting fish, squid-like cephalopods, marine reptiles, and even seabirds. Its bulldog-like jaw and fangs were perfect for slashing and holding—prey was often swallowed head-first.

Famous evidence of its gluttony: Over a dozen specimens preserve undigested stomach contents. The most iconic is a 4-meter (13-foot) X. audax with a complete 1.8–2-meter (6-foot) Gillicus arcuatus (another fish) inside, suggesting the predator died from overeating or the prey’s struggles rupturing its stomach.

It faced threats from larger mosasaurs and sharks like Cretoxyrhina—one fossil even shows Xiphactinus remains inside a shark.

The iconic “fish-within-a-fish” fossil, showcasing Xiphactinus’s predatory habits:

Step 4: Discovery and Fossil Record – From Niobrara Chalk to Global Finds

First described in 1870 by Joseph Leidy from Niobrara Chalk fossils in Kansas, X. audax remains are primarily from the U.S. (Kansas, Texas, Alabama, Georgia), with rarer finds in Canada, Venezuela, Europe, Australia, and recently Argentina (2020s). The Smoky Hill Chalk yields the best-preserved specimens due to fine sedimentation.

Notable mounts include originals/casts at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History (Hays, Kansas—the “fish-within-a-fish”), American Museum of Natural History (New York), Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum, Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto), and traveling exhibits like “Savage Ancient Seas.”

Another impressive full skeleton on display:

Step 5: Extinction and Evolutionary Significance – End of an Era

Xiphactinus vanished in the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction (66 million years ago), likely due to the asteroid impact’s effects on marine food chains. As a teleost, it represents advanced bony fish evolution, bridging ancient forms to modern predators.

Step 6: Modern Interpretations and Educational Value – Bringing the Past to Life

Exhibits like this use casts for dynamic poses, educating on Cretaceous marine ecosystems. For hands-on learning, view 3D models online or visit Niobrara sites (with permits). Ethical note: Support museums preserving originals.

In summary, the image embodies Xiphactinus audax as the “monster fish” of ancient seas—a swift, savage hunter whose fossils continue to thrill and inform. This tutorial transforms a museum glance into deep appreciation of prehistoric ocean life.