Megalodon Teeth: Relics of the Ocean’s Greatest Predator – A Detailed Paleontological Tutorial from Museum Displays

Description:

The image showcases a stunning museum exhibit of fossilized teeth from the extinct giant shark Otodus megalodon (commonly known as Megalodon), mounted on individual stands under dramatic lighting in a glass case. A prominent label reads: “Extinct Giant White Shark / Otodus megalodon / Miocene/Pliocene Epochs / 5 to 15 million years ago / Hawthorne Formation / Coastal Region of the Carolinas.” This professional tutorial-style guide explores these iconic fossils step-by-step, ideal for educators, collectors, researchers, and enthusiasts. We’ll cover identification, anatomy, geological context, size implications, and collection ethics, drawing on the exhibit’s details to provide an in-depth resource for understanding one of the most formidable predators in Earth’s history.

Step 1: Identifying the Fossils in the Exhibit – Overview of Megalodon Teeth

The display features several large, triangular teeth with serrated edges, varying in color from creamy white roots to dark gray or brownish enamel crowns—a classic preservation pattern in shark teeth fossils. These are anterior and lateral teeth from Otodus megalodon, a species that lived from approximately 23 to 3.6 million years ago, spanning the Miocene and Pliocene epochs. The label’s reference to 5 to 15 million years ago aligns with Pliocene deposits in the Carolinas.

Megalodon teeth are among the most sought-after fossils due to their size, durability, and abundance compared to the shark’s cartilaginous skeleton, which rarely fossilizes. In the image, the teeth range from about 4 to 6 inches (10–15 cm) in slant height, typical of high-quality specimens from the southeastern U.S. The Hawthorne Formation, mentioned on the label, is a Miocene-age geological unit rich in marine fossils, exposed along rivers and coasts in South Carolina and North Carolina.

For a similar museum display of multiple Megalodon teeth:

Step 2: Anatomy of a Megalodon Tooth – Structure and Function

Examine a Megalodon tooth as if under a magnifying glass. Each tooth consists of a crown (the visible cutting portion) coated in enamel, a root for anchorage in the jaw, and a bourlette (a dark band at the crown-root junction). The broad, triangular shape with fine serrations along the edges—visible in the foreground teeth—evolved for slicing through flesh and bone of large prey like whales.

Unlike modern great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), often considered close relatives, Megalodon teeth lack the nutrient foramen (central hole) in some positions and feature thicker roots for supporting immense bite forces. The dark coloration results from mineralization by iron and other elements in sedimentary environments, while lighter areas indicate less exposure.

Tutorial tip: To identify authenticity, check for natural serrations (uniform and sharp) versus modern replicas (often smoother). Real fossils show wear from use, such as chipped tips or polished edges from feeding.

Here’s a close-up view highlighting enamel texture and serrations:

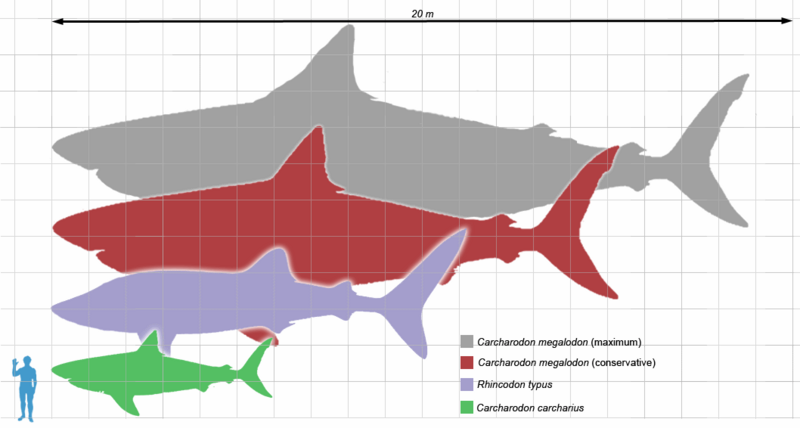

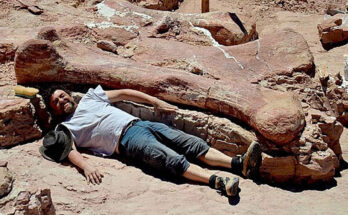

Step 3: Size and Scale – Inferring the Shark’s Immensity from Teeth

Megalodon teeth provide the primary evidence for estimating the shark’s size, as no complete skeletons exist. Paleontologists use regression formulas based on tooth enamel height or crown width to calculate body length. A 6-inch (15 cm) tooth, like those in the exhibit, suggests a shark of 50–60 feet (15–18 meters) in length, with the largest known teeth (over 7 inches/18 cm) implying individuals up to 67 feet (20 meters) or more.

Compare this to modern great whites: Their teeth rarely exceed 3 inches (7.6 cm). This dramatic difference underscores Megalodon’s status as the largest shark ever.

Visual scale comparison between Megalodon and great white shark teeth:

Step 4: Geological and Regional Context – The Carolinas as a Fossil Hotspot

The label specifies the Hawthorne Formation and coastal Carolinas, a prime location for Megalodon teeth due to ancient shallow seas teeming with marine life. During the Miocene-Pliocene, warm waters covered much of the southeastern U.S., and rivers like the Cooper in South Carolina erode phosphate-rich beds, exposing fossils on beaches and riverbanks.

Divers and collectors frequently find these teeth in blackwater rivers or offshore dredge sites. The region’s specimens often exhibit excellent preservation with vibrant colors from phosphate mineralization.

Examples of Megalodon teeth collected from North Carolina coastal areas:

Step 5: Paleobiology and Extinction – Life as an Apex Predator

Megalodon was a cosmopolitan superpredator, preying on whales, seals, and large fish with a bite force estimated at 10–18 tons—far exceeding any modern animal. Nursery areas in warm coastal waters, like those of the ancient Carolinas, supported juveniles.

The shark went extinct around 3.6 million years ago, likely due to cooling oceans, declining prey populations (e.g., smaller whales), and competition from emerging predators like orcas. Recent studies refine the timeline using zinc isotope analysis in teeth.

Step 6: Collecting and Ethics – Responsible Fossil Appreciation

Museum exhibits like this use ethically sourced specimens to educate without depleting sites. For personal collecting, obtain permits for public lands, buy from reputable dealers with provenance, and avoid illegal exports. Replicas are excellent for study—many museums use casts for interactive displays.

Tutorial exercise: Measure a tooth’s slant height (from tip to root corner) and use online calculators (e.g., from the Florida Museum) to estimate shark size.

In summary, this exhibit captures the awe-inspiring legacy of Megalodon through its most enduring remains: teeth that once armed the jaws of history’s ultimate ocean hunter. Whether in a museum case or riverbed find, these fossils connect us to a vanished world of giants.