Inostrancevia: The Saber-Toothed Apex Predator of the Permian – A Comprehensive Paleontological Tutorial Inspired by Moscow’s Museum Exhibit

Description:

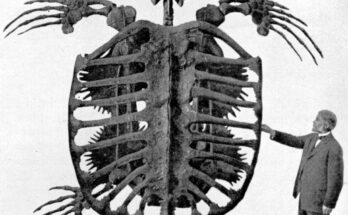

Delving into the prehistoric world of therapsids, the image captures a captivating exhibit at the Borissiak Paleontological Institute’s Yuri A. Orlov Paleontological Museum in Moscow, Russia. This professional guide, structured as a step-by-step tutorial, explores the genus Inostrancevia—a massive, saber-toothed gorgonopsid that dominated Late Permian ecosystems approximately 259 to 252 million years ago. The display features a nearly complete fossil skeleton laid out on a sandy base, accompanied by wall-mounted artifacts including skull fragments, historical photographs, informational plaques in Russian, and artistic reconstructions depicting dramatic predator-prey interactions. Ideal for educators, researchers, students, and paleo-enthusiasts, this detailed overview equips you with the knowledge to interpret similar exhibits, understand evolutionary significance, and even replicate elements for educational purposes. We’ll break it down systematically, drawing on fossil evidence, scientific studies, and museum curation practices.

Step 1: Identifying the Exhibit and Specimen – Contextualizing the Image

The image showcases a classic paleontological display from the Orlov Paleontological Museum, renowned for its extensive collection of Permian fossils from Russian localities. The centerpiece is a near-complete skeleton of Inostrancevia alexandri, one of the most iconic specimens in the museum’s holdings. This skeleton, likely PIN 1758 or a related cast, measures approximately 3 to 3.5 meters (10 to 11.5 feet) in length, with a skull around 45 to 60 centimeters (18 to 24 inches) long. The bones are arranged in a semi-articulated pose on a simulated sedimentary bed, emphasizing the animal’s quadrupedal stance and robust build. The skull, positioned prominently in the foreground, reveals elongated canines—saber-like teeth up to 15 centimeters (6 inches) long—curved slightly backward with fine serrations for efficient prey capture.

Surrounding the skeleton, the wall features complementary elements: framed black-and-white photographs, possibly of the discoverer Vladimir Amalitsky or excavation sites; isolated fossil fragments like a horned skull (potentially from a pareiasaur such as Scutosaurus) and other cranial pieces; and detailed pencil drawings reconstructing Inostrancevia in action. One large illustration depicts the predator ambushing a herbivorous Scutosaurus, highlighting its hunting prowess in a lush Permian landscape. Informational plaques in Russian provide scientific context, including genus classification, geological period, and discovery details. This setup is typical of Russian paleontological museums, where exhibits blend original fossils with artistic interpretations to narrate evolutionary stories.

For visual reference, here’s a similar skeleton display from the museum:

Step 2: Anatomy of Inostrancevia – Breaking Down the Skeleton

To appreciate the fossil like a paleontologist, examine its anatomy section by section, as if conducting a virtual dissection. Inostrancevia was a gorgonopsid therapsid, a group of synapsids (mammal precursors) characterized by a single temporal fenestra in the skull—a key evolutionary step toward mammalian traits. The skull in the image is broad and elongated, with large oval openings behind the eyes for powerful jaw muscles, small orbits indicating side-facing eyes for wide peripheral vision, and a raised snout for enhanced olfaction via nasal turbinals. Dentition is specialized: four upper incisors (unique among gorgonopsians), massive canines for slashing, and reduced post-canine teeth focused on the maxilla for shearing flesh.

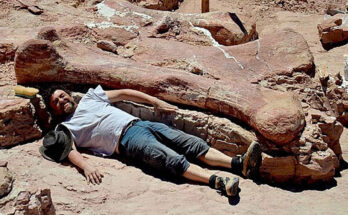

The postcranial skeleton reveals a robust, long-limbed build weighing up to 300–400 kilograms (660–880 pounds). Forelimbs show outward-turned elbows, suggesting a sprawling yet efficient gait; the scapula is plate-like for muscle attachment; and the hindlimbs are more upright, hinting at proto-mammalian locomotion. Feet are plantigrade with symmetrical, clawed phalanges for traction on varied terrain. The vertebrae and ribs form a sturdy torso, while the tail, though incomplete in many fossils, likely provided balance.

Tutorial tip: When studying such skeletons, note preservation quality—here, the bones are well-mineralized from Permian river deposits, preserving fine details like tooth serrations. Use 3D scanning tools (e.g., free software like MeshLab) to model replicas from photos for deeper analysis.

Step 3: Discovery and Historical Context – Tracing the Fossils’ Journey

Inostrancevia’s story begins with its discovery in 1899 by Russian geologist Vladimir Prokhorovich Amalitsky along the Northern Dvina River in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. Excavations from 1899 to 1914 unearthed two near-complete skeletons (PIN 1758 and PIN 2005/1578), the first gorgonopsian remains from Russia, including rare postcranial elements. Amalitsky described the genus posthumously in 1922, naming it after his mentor Alexander Inostrantsev. Additional species like I. latifrons (from the same site) and I. uralensis (from Orenburg Oblast) followed, though some classifications are debated. Recent finds extend its range to Africa, including South Africa (2010–2011), Mozambique (2025), and Tanzania (2024), suggesting migration during Pangea’s formation.

The Moscow museum’s exhibit honors this legacy, with the displayed skeleton being one of the original Amalitsky finds or a high-fidelity cast. Wall elements likely include Amalitsky’s portraits and site photos, underscoring the historical significance of Russian paleontology.

Step 4: Paleobiology and Ecology – Reconstructing Life and Behavior

As an apex predator in Permian floodplains, Inostrancevia hunted large herbivores like dicynodonts and pareiasaurs (e.g., Scutosaurus), using ambush tactics. Its saber teeth delivered slashing bites, with a wide jaw gape (up to 90 degrees) for fatal wounds, though not for bone-crushing. Locomotion combined sprawling forelimbs with erect hindlimbs, enabling a “high walk” for speed and agility—estimates suggest bursts up to 20–30 km/h (12–19 mph). Sensory adaptations included keen smell but limited binocular vision.

The exhibit’s drawing vividly illustrates this: Inostrancevia pouncing on Scutosaurus, claws extended and jaws agape, amid ferns and conifers. Such reconstructions, often by artists like Sergey Krasovskiy, are based on biomechanical models and comparative anatomy.

Enhance your understanding with this artistic depiction:

Inostrancevia vanished during the Permian-Triassic extinction, linked to volcanic activity from the Siberian Traps, paving the way for dinosaurs and mammals.

Step 5: Museum Exhibits Worldwide and Modern Interpretations – Global Perspectives

While the Orlov Museum houses the most complete originals, casts appear globally: a mounted skeleton at the Museo delle Scienze in Trento, Italy; displays at the Field Museum in Chicago; and traveling exhibits like “Permian Monsters” at venues such as the Cranbrook Institute of Science. Other U.S. museums, like the Arizona Museum of Natural History and Houston Museum of Natural Science, feature gorgonopsid skeletons identified as Inostrancevia.

Modern studies use CT scans for internal anatomy and finite element analysis for bite force simulations. For hands-on learning, 3D-print models from open-source files on sites like Thingiverse, or visit virtual tours of the Moscow museum.

Step 6: Educational Applications and Conservation – Applying the Knowledge

This exhibit teaches therapsid evolution’s role in mammalian origins, emphasizing biodiversity loss during mass extinctions—relevant to today’s climate challenges. Tutorial exercise: Sketch your own reconstruction using the image as reference, noting proportions (e.g., skull 1/6 body length). Ethically, support museums by advocating fossil repatriation and sustainable digging.

In summary, the image encapsulates Inostrancevia’s legacy as a bridge between reptiles and mammals, blending science and art in a timeless display. Explore further with this mounted skeleton example: