Discovering the Megalodon Tooth: Anatomy, Fossil Features, and Post-Mortem History – A Hands-On Identification Tutorial

Description: Close-Up Guide to Authentic Otodus megalodon (Formerly Carcharocles megalodon) Fossil Teeth – From Serrations to Borings

Welcome to this in-depth tutorial on one of the most iconic fossils in paleontology: the massive tooth of the prehistoric super-predator Otodus megalodon (often still referred to as Carcharocles or Carcharodon megalodon). The photograph captures a well-preserved, hand-held specimen showcasing classic features that make these teeth instantly recognizable and highly sought after by collectors, educators, and researchers alike. This guide is perfect for fossil hunters, amateur paleontologists, museum enthusiasts, or anyone curious about apex predators from the Miocene to Pliocene epochs (approximately 23–3.6 million years ago). We’ll dissect the tooth’s anatomy, explain key identification markers, explore natural wear and damage (including the prominent holes), discuss fossilization processes, and provide tips for distinguishing genuine specimens. By the end, you’ll be equipped to appreciate—or even identify—your own megalodon tooth finds.

Step 1: Overview of the Specimen – What You’re Looking At

The image shows a triangular, robust fossil tooth cradled in a person’s hand against a natural outdoor background of green foliage and dappled sunlight. This setting highlights the tooth’s size (likely 4–6 inches based on hand proportions) and three-dimensional texture. Key visual elements include:

- Overall Shape: Broad, symmetrical triangle with a pointed cusp and wide root base—hallmarks of an anterior (front) tooth position in the jaw.

- Color Variation: Mottled grayish-blue enamel transitioning to brownish-orange root and patches, with creamy-tan weathering on edges. This multi-toned appearance results from mineral uptake (e.g., iron oxides, manganese) during fossilization in different sediments—common in coastal or riverine deposits like those in the southeastern U.S. (South Carolina, Florida) or Peru.

- Surface Details: Fine serrations along the cutting edges, polished enamel on the crown, rougher root texture, and several distinct circular-to-oval holes penetrating the enamel and root.

This is a classic authentic example—no artificial polishing or repair evident—displaying both predatory adaptations and post-depositional history.

Step 2: Anatomical Breakdown – Key Features of a Megalodon Tooth

Megalodon teeth evolved as “ultimate cutting tools” for slicing through large marine mammals like whales. Unlike modern great white sharks (coarser serrations, thinner profile), megalodon teeth are thicker, more robust, and finely serrated for efficient flesh removal.

- Crown (Blade): The upper triangular portion, covered in smooth, glossy enamel (darker gray-blue here). Fine, saw-like serrations run along both edges—visible as tiny notches. These are much finer and more numerous than great white serrations, optimized for cutting rather than gripping. In perfect specimens, serrations remain razor-sharp; wear here suggests natural abrasion from use or tumbling in ancient rivers/seas.

- Bourlette (Dental Band): The distinct chevron- or V-shaped dark band at the crown-root junction. This exposed orthodentine (dentin-like layer) is a diagnostic trait unique to megalodon among large lamniform sharks. In the photo, it’s subtly visible as a transitional zone.

- Root: Thick, bilobed base with nutrient foramina (small natural pores for blood vessels during life). The root appears porous and brownish, typical of mineralization. Roots anchor the tooth in cartilage jaws—sharks continuously replace teeth, shedding thousands over a lifetime.

- Size and Robustness: This tooth’s heft (dense due to fossilization) and proportions indicate a large individual—possibly 40–50 feet long. Larger teeth (>6 inches) are rarer and more valuable.

Step 3: The Prominent Holes – Bioerosion and Post-Mortem History

The most striking feature in the photo is the series of circular holes (several millimeters wide) piercing the enamel and root. These are not damage from the shark’s lifetime or manufacturing defects—they are classic examples of bioerosion after the tooth was shed.

- Causes: After detachment, the tooth sank to the seafloor. Marine organisms colonized it:

- Boring clams (Pholadidae family, e.g., piddocks or angel wings): These bivalves mechanically grind or chemically dissolve into hard substrates (including bone, shell, and dense fossils) for protection. Their borings create smooth-walled, flask-shaped holes (Gastrochaenolites trace fossils), often narrower at the entrance.

- Other culprits: Moon snails (Naticidae), harp snails, or polychaete worms may produce acidic secretions dissolving calcium phosphate. Orange-brown spots/patches often accompany these, from iron staining or acidic etching.

- Significance: These holes document a “second life” on the ancient seabed—evidence of a healthy marine ecosystem where shed predator teeth became habitat for smaller invertebrates. Similar borings appear on whale bones from the same era.

Such features enhance authenticity: pristine, hole-free teeth are rarer (and pricier), but bioeroded examples tell a fuller taphonomic (preservation) story.

Step 4: Fossil vs. Fake – Authentication Tips

With megalodon teeth commanding high prices, fakes abound. Use this specimen as a benchmark:

- Weight & Density: Genuine fossils feel heavy (mineral replacement increases density). Lightweight = likely cast/resin.

- Serrations & Texture: Fine, irregular natural serrations (not uniform/machine-made). Look for subtle wear, pits, or micro-cracks under magnification.

- Color & Variation: Natural gradients from sediment minerals—no uniform bright/white (modern teeth) or overly vibrant dyes.

- Root & Bourlette: Well-defined, nutrient foramina present; intact bourlette adds value.

- Imperfections: Natural flaws (peeling enamel, chips, borings) indicate authenticity. Perfect symmetry often signals restoration or replica.

Pro tip: Compare to verified museum specimens or use AI identification apps trained on thousands of examples.

Step 5: Paleontological and Cultural Context

Otodus megalodon ruled oceans for ~20 million years as the apex predator, preying on baleen whales and other large fauna. Its disappearance (~3.6 Ma) likely stemmed from cooling oceans, prey loss, and competition. Teeth are the primary fossils (cartilaginous skeleton rarely preserves), found worldwide in shallow marine deposits.

Culturally, these “megatooth” fossils inspire awe—symbols of prehistoric power. Collectors prize color variants (e.g., turquoise, black), size, and condition. This hand-held view reminds us: every tooth represents a lost giant and a snapshot of ancient marine life.

Step 6: Visual Comparisons for Deeper Understanding

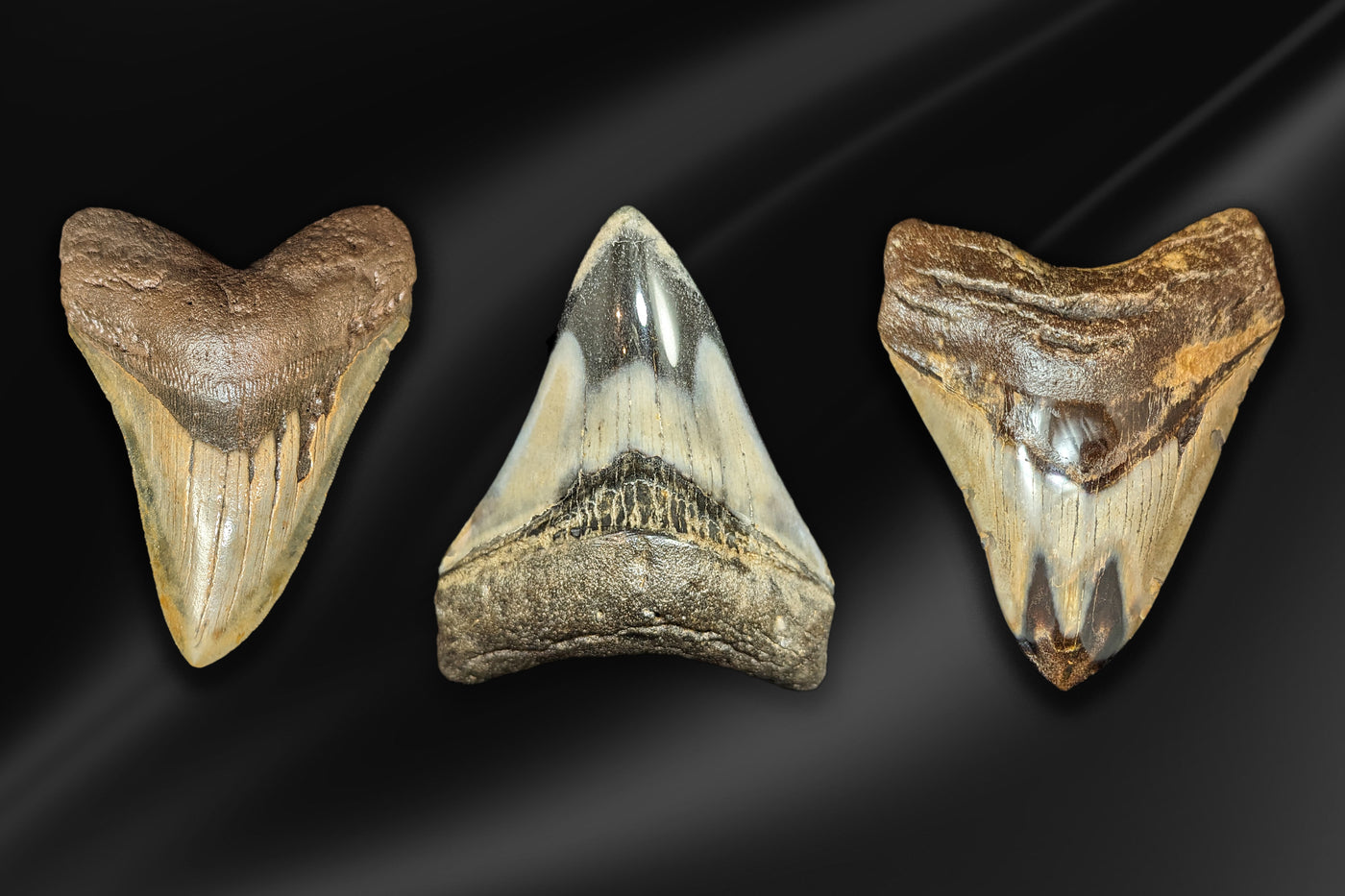

To better appreciate details like serrations, root structure, and bioerosion, here are complementary authentic megalodon tooth images:

These show variations in size, color, wear, and natural features for side-by-side comparison.

Conclusion: Holding Prehistory in Your Hand

This photographed tooth is more than a collectible—it’s tangible evidence of Earth’s most formidable shark and the dynamic seafloor ecosystems it left behind. Whether beachcombing rivers like the Cooper (South Carolina) or studying museum displays, understanding these details deepens appreciation for megalodon’s legacy.

If you’ve found or own a similar tooth, examine it closely: measure serration density, check for borings, and document provenance. Share your own photos or questions below—what feature fascinates you most? Happy hunting!

In the spring of 2016, Black River Fossils happened upon what might be the ultimate spot for finding fossilized shark teeth, including the elusive Megalodon tooth. What’s most exciting is that he took the time to record his visit at this spot, which lasted about a week.

If you enjoy collecting fossils, this video is the stuff you dream about! And there are plenty of nail-biting “please…be whole” moments.