The Cave Bear (Ursus spelaeus): Anatomy, Ecology, Extinction, and Legacy – A Comprehensive Paleontological Guide

Description: Exploring the Mighty Cave Bear – Insights from Prehistoric Fossils and Modern Research

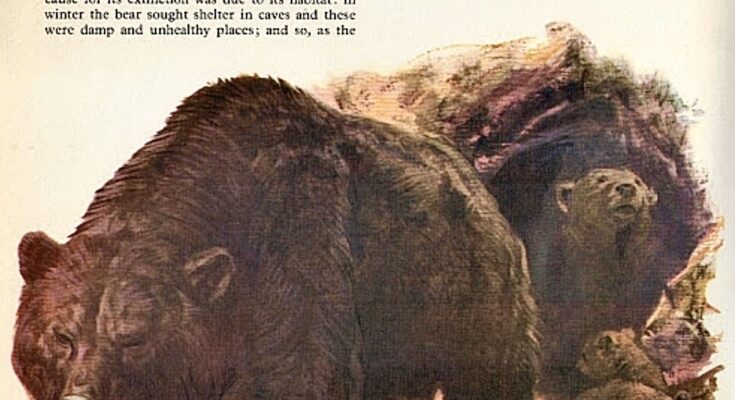

Dive into this detailed tutorial on the Cave Bear (Ursus spelaeus), one of the most iconic and well-documented megafauna species of the Pleistocene epoch. This guide draws from classic illustrations like the one shown—depicting a powerful adult bear with cubs in a rugged, earthy-toned landscape—alongside up-to-date scientific understanding to provide educators, students, fossil enthusiasts, and wildlife history buffs with a thorough exploration. We’ll break down the animal’s physical traits, lifestyle, habitat preferences, reasons for extinction, and enduring traces in the archaeological record. By the end, you’ll appreciate why the cave bear captivates researchers and why its story offers lessons for modern conservation.

Step 1: Introduction to the Cave Bear – Naming, Discovery, and Historical Context

The cave bear, scientifically named Ursus spelaeus (from Latin “ursus” for bear and “spelaeus” for cave), earned its moniker because vast numbers of its fossils have been recovered from European caves, where the animals frequently hibernated. First formally described in 1794 by anatomist Johann Christian Rosenmüller based on bones from the Zoolithenhöhle in Bavaria, Germany, cave bear remains are among the most abundant Pleistocene mammal fossils. So plentiful were they that during World War I, German forces mined cave bear bones for phosphates.

The vintage illustration captures the essence of the species: a massive, dark-brown adult striding forward with a scowling muzzle, accompanied by smaller cubs, set against a rocky backdrop. This artistic rendering emphasizes the bear’s imposing size and family-oriented behavior, evoking the Pleistocene landscapes of Europe. Unlike many megafauna, the cave bear’s extinction around 24,000–28,000 years ago (during the Last Glacial Maximum) predates the final wave of Ice Age extinctions, making it a key case study in paleobiology.

Step 2: Physical Anatomy – Size, Build, and Distinctive Features

The cave bear was one of the largest terrestrial carnivorans of its time, comparable to or slightly exceeding the largest modern brown bears (Ursus arctos) and Kodiak bears.

- Size and Dimensions: Adult males typically measured 2.1–3.5 meters (7–11.5 feet) in length, stood 1.5–1.7 meters (5–5.7 feet) at the shoulder when on all fours, and could reach over 3 meters tall when standing on hind legs. Weights ranged from 400–590 kg (880–1,300 lb) for males, with exceptional specimens possibly nearing 1,000 kg. Females were smaller, at 225–250 kg (500–550 lb) and 1.4–1.57 meters shoulder height. In the illustration, the foreground adult appears stocky and powerful, with broad shoulders and a low-slung posture that highlights its robust build.

- Skull and Dentition: The head was enormous, featuring a steeply descending forehead, broad dome-like skull, and a short, scowling muzzle. The braincase was relatively small compared to body size. Teeth were adapted for a primarily vegetarian diet: large molars for grinding tough plant material, reduced premolars (sometimes absent), and massive canines. Studies of dental microwear and isotopes confirm opportunistic omnivory—mostly plants, roots, berries, and seeds, supplemented by insects, larvae, carrion, or occasional meat.

- Limbs and Claws: Forelimbs bore huge, curved claws ideal for digging vegetation, stripping bark, or excavating insect nests—as noted in older accounts emphasizing larvae consumption. Hind legs were strong, supporting bipedal standing (over 3 meters tall). The plantigrade stance (walking on soles) is evident in fossil pathologies showing arthritis from prolonged cave use.

- Body and Fur: The illustration portrays thick, dark fur suited to cold climates, with a muscular torso and powerful neck. Fossils indicate sexual dimorphism, with males more heavily built.

Comparative note: While similar in size to modern brown bears, cave bears had denser bones, a more herbivorous skull morphology, and larger sinuses that aided prolonged hibernation but limited dietary flexibility.

Step 3: Habitat, Behavior, and Hibernation – Life in Pleistocene Europe

Cave bears ranged across most of Europe (from Spain to western Russia), parts of Asia, and possibly northern Middle East regions during the Middle to Late Pleistocene (roughly 300,000–24,000 years ago).

- Cave Dependence: Unlike brown bears, which use caves sporadically, cave bears relied heavily on them for winter hibernation. Damp, enclosed spaces led to high mortality from diseases like arthritis and tuberculosis—evidenced by abundant deformed bones in cave deposits. As the text notes, caves became “their tomb” due to unhealthy conditions.

- Diet and Foraging: Primarily herbivorous, browsing on vegetation, but opportunistic: huge claws stripped insects and larvae from logs or soil. Isotopic and microwear studies confirm flexibility, though specialized molars favored softer plants over tough or meaty fare.

- Social and Reproductive Behavior: The illustration shows an adult with cubs, suggesting family groups. Females likely gave birth in winter dens, with cubs staying close for protection.

- Claw Marks – Lasting Evidence: In many caves (e.g., Chauvet, Pech-Merle, recent Spanish finds), walls bear deep, parallel claw scratches up to 3 meters high—marks from standing bears sharpening claws, marking territory, or stretching. These “ursine drawings” are widespread and unmistakable, preserved for millennia.

Step 4: Extinction – Multifactorial Causes and Modern Insights

The cave bear vanished around 24,000–28,000 years ago, earlier than most Pleistocene megafauna. No single cause explains it; research points to a combination:

- Climate Change: The Last Glacial Maximum reduced vegetation, challenging herbivorous specialists. Enlarged sinuses aided long hibernation but restricted biting force, limiting dietary shifts to meat.

- Habitat Competition: Heavy reliance on caves for hibernation clashed with expanding Neanderthal and modern human populations, who occupied prime shelters. Humans may have hunted bears sporadically, but competition for space was likely greater.

- Dietary Inflexibility and Decline: Genetic studies show population decline starting ~50,000 years ago, accelerated by human expansion rather than climate alone. Mitochondrial DNA reveals low genetic diversity and slow recovery from bottlenecks.

- Pathologies: Frequent bone diseases from damp caves weakened populations over generations.

Unlike adaptable brown bears, cave bears couldn’t pivot effectively, sealing their fate.

Step 5: Paleontological and Cultural Significance – Why It Matters Today

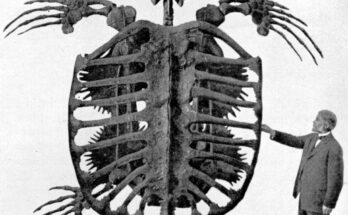

Cave bear fossils offer unparalleled insights: bone beds reveal population dynamics, isotopes track diet shifts, and ancient DNA shows divergence from brown bears (with some modern bears carrying trace cave bear genes). Sites like Drachenhöhle (Austria) yielded tons of bones, underscoring abundance.

Culturally, cave bears influenced human imagination—from folklore to Jean Auel’s Clan of the Cave Bear. Claw-marked walls blend animal and human traces in painted caves, highlighting shared Ice Age spaces.

For educational activities: Compare skull models (cave vs. brown bear), analyze claw-mark photos, or simulate hibernation impacts using biomechanics. Visit virtual tours of Chauvet Cave or examine fossils at museums like the Natural History Museum in Vienna.

Conclusion: Lessons from the Cave Bear

The cave bear exemplifies how specialization—in diet, habitat, and physiology—can prove fatal amid rapid environmental and anthropogenic change. Its story reminds us that even formidable species are vulnerable when pressures converge. As modern bears face habitat loss and climate shifts, understanding Ursus spelaeus informs conservation: preserve connectivity, reduce human-bear conflict, and protect genetic diversity.

Use this illustration as inspiration—sketch reconstructions, debate extinction hypotheses, or explore local cave sites. Share your thoughts or findings in the comments—what aspect of the cave bear fascinates you most?