Exploring Ammonites: Iconic Fossils of Ancient Seas – A Detailed Paleontological Tutorial Inspired by Museum Exhibits

Description:

In the captivating realm of paleontology, ammonites stand out as some of the most recognizable and scientifically significant fossils, offering windows into Earth’s ancient oceans. This comprehensive guide, drawn from the provided image of a museum display, serves as a tutorial-style exploration for educators, students, researchers, and enthusiasts. The image depicts a dimly lit exhibit hall where a visitor crouches intently before a showcase of large, spiraled ammonite shells alongside other prehistoric marine fossils, with a stegosaurus skeleton looming in the background. We’ll break this down step-by-step, covering identification, anatomy, evolution, famous specimens, and modern interpretations, to provide a professional, in-depth resource for website posting. By the end, you’ll have the tools to appreciate these extinct cephalopods as if curating your own exhibit.

Step 1: Identifying the Fossils in the Image – An Overview of Ammonites and Their Museum Context

The focal point of the image is a collection of ammonite fossils, extinct marine mollusks belonging to the subclass Ammonoidea within the class Cephalopoda. These creatures, related to modern squid, octopuses, and nautiluses, thrived from the Devonian period (around 419 million years ago) to the end of the Cretaceous (66 million years ago), when they vanished in the mass extinction event that also claimed the non-avian dinosaurs. The large, curved shell in the center resembles specimens of Parapuzosia or similar giant ammonites, with its chambered, coiled structure prominently displayed under spotlights.

Ammonites are characterized by their planispiral (flat-coiled) shells, though some evolved heteromorph (irregular) forms like straight or helical shapes. In the image, smaller coiled and possibly heteromorph examples line the shelf, accompanied by other fossils such as crinoids or bivalves, creating a timeline of marine evolution. The visitor’s pose—kneeling to read informational plaques—highlights the educational aspect of such exhibits, often found in renowned institutions like the Natural History Museum in London, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York, or the LWL-Museum of Natural History in Münster, Germany. These plaques typically detail geological ages, discovery sites, and ecological roles, encouraging close inspection as shown.

To visualize a similar exhibit, consider this large ammonite display:

Step 2: Anatomy of Ammonites – Dissecting the Shell and Soft Parts

Understanding ammonite anatomy is key to appreciating their fossils, much like a tutorial in biological dissection. The shell, composed of aragonite (a form of calcium carbonate), was divided into chambers by septa—wavy partitions that strengthened the structure against water pressure. The animal lived in the outermost chamber (body chamber), using a siphuncle—a tube-like structure—to regulate buoyancy by pumping gas and liquid in and out, similar to a submarine’s ballast system.

The shell’s outer surface often featured ribs, spines, or keels for hydrodynamic efficiency or defense. Internally, suture lines—where septa met the shell wall—evolved from simple (straight) in early species to complex (frilled) in later ones, aiding in species identification. Soft tissues are rarely preserved, but exceptional fossils reveal tentacles, ink sacs, and even digestive systems, indicating ammonites were active predators with jet propulsion for movement. Reproductive anatomy remains elusive, but recent studies suggest dimorphism (males smaller than females) and egg-laying behaviors.

In the image, the central ammonite’s polished cross-section reveals these chambers, a common preparation technique in museums to educate on internal structure. For hands-on learning, paleontologists use CT scans or 3D modeling to reconstruct these features without damaging originals.

Step 3: Evolutionary History – From Origins to Extinction

Ammonites’ evolution spans over 350 million years, making them excellent index fossils for dating rock layers. They originated in the Early Devonian from bactritoid nautiloids, rapidly diversifying into over 10,000 species. Key trends include increasing septal complexity for better buoyancy control and shell shape variations adapting to different ocean niches—planktic swimmers, benthic crawlers, or reef dwellers.

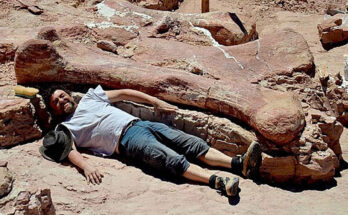

They survived multiple extinctions, including the Permian-Triassic event, but faced iterative crises, rebounding with new forms each time. By the Cretaceous, giants like Parapuzosia reached diameters of up to 2.5 meters (8 feet), as seen in some museum casts. Their demise coincided with the Chicxulub impact, ocean acidification, and competition from emerging fish groups.

Tutorial tip: To trace evolution, examine suture patterns—start with nautiloid-like goniatites (simple sutures), progress to ceratites (wavy), and end with ammonites proper (highly frilled). The image’s array of shells likely illustrates this progression.

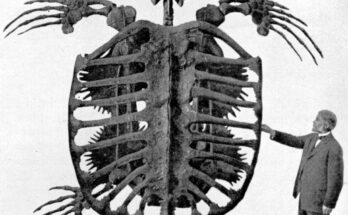

Step 4: Famous Specimens and Museum Displays – Global Highlights

Museums worldwide house iconic ammonites, mirroring the image’s exhibit. The world’s largest known specimen, a Parapuzosia seppenradensis measuring 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) in diameter, resides at the LWL-Museum of Natural History in Münster, Germany—a colossal Late Cretaceous example from Westphalia. In Japan, the Mikasa City Museum boasts over 1,000 ammonites, including the famous heteromorph Nipponites mirabilis and a 1.3-meter giant from Hokkaido.

The AMNH features an iridescent Placenticeras from Alberta, Canada, with opal-like shell preservation. The Smithsonian’s NMNH displays diverse collections for studying extinction patterns. Antarctic specimens at AMNH, like the 2-meter Diplomoceras, highlight polar marine life. In the UK, the NHM in London showcases William Smith’s early 19th-century collection, including Britain’s oldest ammonites.

The image evokes these displays, with its mix of sizes and the stegosaurus adding a terrestrial contrast. For a closer look at a record-breaker:

Step 5: The Visitor’s Experience – Interpreting the Image as a Learning Moment

The crouched figure in the image symbolizes human fascination with deep time. Museums design such exhibits with low lighting to evoke mystery, interactive plaques for context, and spatial arrangements to guide narrative flow—from small, early forms to giant Cretaceous apexes. This setup encourages active engagement, as the person demonstrates by pondering the fossils up close.

Tutorial application: When visiting, note locality labels (e.g., Jurassic Coast, UK, for many European specimens) and use apps like the NHM’s digital guides for augmented reality views. Ethical note: Fossils like these are often casts to preserve originals in storage.

Step 6: Modern Study and Cultural Significance – Beyond the Exhibit

Today, ammonites inform climate reconstructions via isotope analysis of shells, revealing ancient ocean temperatures. Biomechanical models simulate their swimming, while 3D printing allows replicas for education. Culturally, they’ve inspired myths (e.g., “snake stones” in folklore) and art.

For further exploration, visit the Dinosaurier Museum Altmühltal’s “Ammonite Masterpieces” exhibit or study Canadian gems like Placenticeras meeki. To replicate at home, source ethical fossils or use free 3D models from sites like Sketchfab.

In essence, the image captures the timeless allure of ammonites—evolutionary marvels preserved in stone. This tutorial equips you to delve deeper, transforming a simple glance into profound understanding. For another stunning example: