In landscape architecture, site planning, and sustainable design, understanding wind behavior is crucial for creating comfortable outdoor spaces, reducing energy costs, and protecting structures from harsh weather. Trees are powerful natural tools that can both respond to prevailing winds (developing characteristic shapes over time) and actively modify wind patterns to create sheltered microclimates.

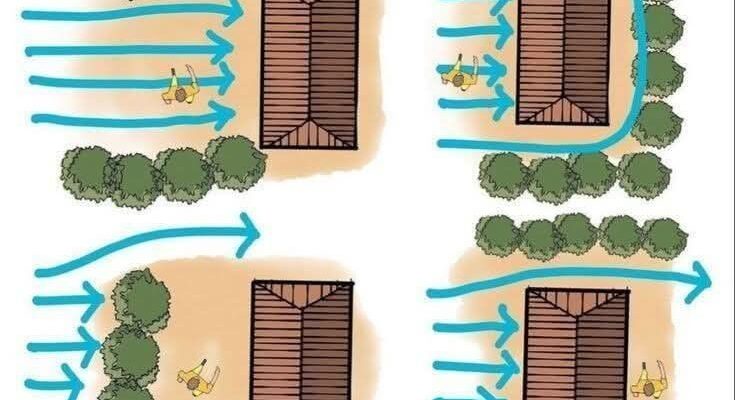

This illustrated tutorial explores the dual relationship between trees and wind, showing how strategic tree placement influences airflow around a building. The diagrams demonstrate four common planting configurations and their effects on wind deflection, channeling, and shelter creation—perfect for architects, landscape designers, homeowners, and permaculture enthusiasts.

Key Concepts Covered

- Wind-flagged trees (also called flag-form or anemomorphic trees): Trees permanently shaped by consistent prevailing winds, with branches and foliage leaning or streamlined away from the dominant wind direction.

- Windbreaks and shelterbelts: Intentional tree plantings designed to slow, redirect, or block wind, reducing velocity by 50–90% in the protected zone.

- Aerodynamic effects: How tree density, arrangement, height, and shape determine whether wind is deflected over, around, channeled through, or significantly calmed.

Breakdown of the Four Planting Scenarios

- Dense Row Upwind – Direct Deflection (Top Left) A solid, continuous row of trees (e.g., evergreens or dense deciduous species) planted perpendicular to the prevailing wind creates a strong barrier.

- Wind hits the trees and is forced up and over the canopy.

- Behind the barrier, a large low-velocity zone forms immediately downwind, protecting the building and outdoor area.

- Ideal for blocking cold winter winds or creating a calm patio zone.

- Visual tip: Notice the straight, parallel arrows becoming disrupted and reduced right behind the house.

Here are real-world examples of trees permanently shaped by strong prevailing winds:

- U-Shaped Tree Arrangement – Channeling & Shelter (Top Right) Trees planted in a U-formation around the building (open side facing away from the wind) guide airflow around the structure while creating a protected pocket in the center.

- Wind is diverted sideways and funneled along the sides rather than slamming directly into the facade.

- The building experiences reduced direct pressure, and the interior courtyard remains significantly calmer.

- Excellent for Mediterranean or coastal climates where cooling summer breezes are desired but strong gusts need management.

- Linear Row with Gaps – Partial Permeability (Bottom Left) A single, spaced row or staggered planting allows some wind to pass through while still slowing and lifting the majority.

- This creates a longer but gentler wind shadow zone compared to a solid barrier.

- Prevents extreme turbulence (eddies) that can occur behind impermeable walls.

- Best for moderate wind control, maintaining some natural ventilation.

- Multiple Rows or Deep Shelterbelt – Maximum Protection (Bottom Right) Several parallel rows of trees (increasing in height from front to back) form a deep windbreak.

- Wind is gradually slowed and lifted over a larger area, producing the widest and most stable low-velocity zone.

- This configuration offers the strongest overall protection and is commonly used in agricultural shelterbelts, suburban lots, and exposed urban sites.

- Notice how wind arrows spread out and weaken dramatically downwind.

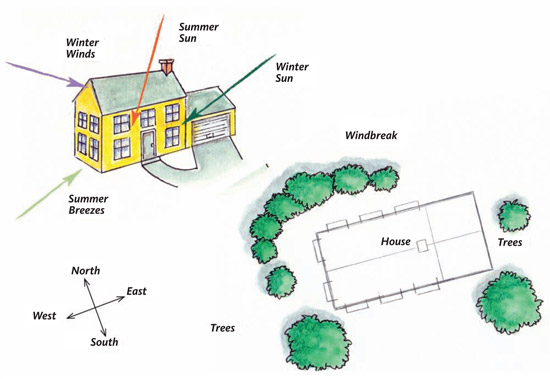

Real-world windbreak designs in action:

Practical Design Guidelines

- Optimal density: 40–60% porosity for most windbreaks (allows some air through to reduce turbulence).

- Height & distance: Place the primary row 3–5 times the mature tree height upwind of the protected area for maximum shelter.

- Species selection: Use dense, wind-tolerant evergreens (e.g., pines, spruces, cedars) for year-round protection; mix with deciduous trees for seasonal variation.

- Avoid common mistakes: Solid walls of trees can create damaging downdrafts or eddies; overly sparse plantings offer little protection.

- Bonus applications: Use these principles for summer cooling (channel breezes toward windows), snow drifting control, noise reduction, and privacy screening.

By thoughtfully positioning trees in relation to prevailing winds, designers can dramatically improve comfort, energy efficiency, and site resilience. Study local wind roses (prevailing direction data) and test configurations with simple models or digital wind simulation tools for best results.

What wind challenges does your site face? Have you used trees as natural windbreaks? Share your experiences or sketches in the comments—we’d love to hear your stories! 🌳💨 #LandscapeArchitecture #SustainableDesign #Windbreak #Permaculture #SitePlanning