Exploring the Pteranodon: The Iconic Flying Reptile of the Cretaceous Skies

Introduction to Pteranodon

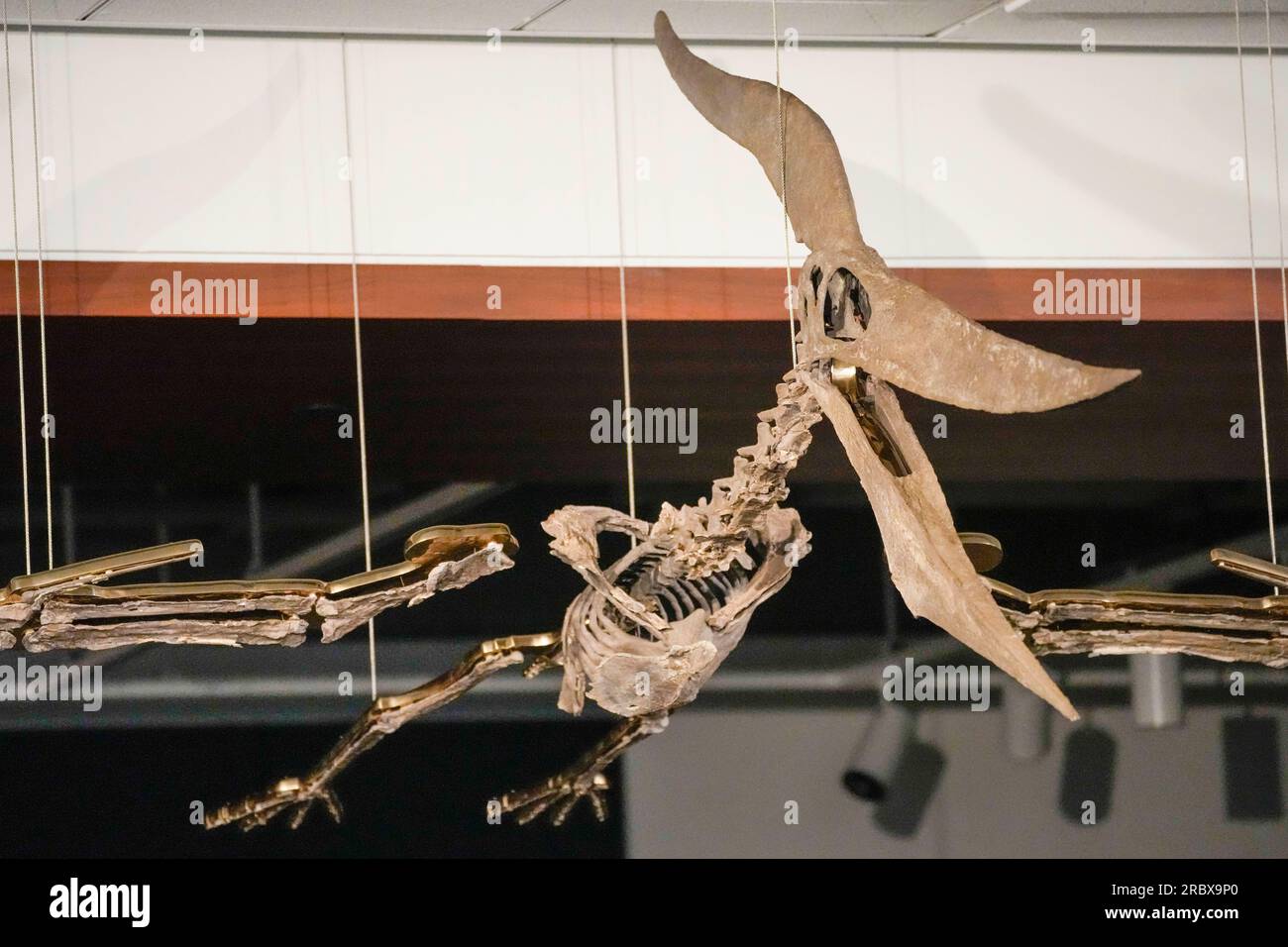

The Pteranodon stands as one of the most recognizable pterosaurs in paleontological history, often mistaken for a dinosaur but actually a flying reptile that soared through the skies during the Late Cretaceous Period, approximately 89 to 70 million years ago. This genus, meaning “toothless wing” in Greek, is celebrated for its impressive wingspan, streamlined anatomy, and distinctive cranial crest. The fossil skeleton captured in the image—a beautifully preserved mount displayed in a museum glass case—exemplifies the elegance and engineering of these ancient aviators. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the discovery, anatomy, habitat, behavior, and modern interpretations of Pteranodon, providing a step-by-step tutorial-like exploration to help enthusiasts and researchers alike appreciate this prehistoric marvel.

This article is structured as a tutorial to build your understanding progressively: starting with historical context, moving to anatomical breakdowns, exploring ecological roles, and concluding with tips for further study or museum visits. Whether you’re a student, hobbyist, or professional, follow along to gain a deeper insight into how Pteranodon fits into Earth’s evolutionary tapestry.

(A close-up of a Pteranodon skeleton suspended in a grand museum hall, showcasing the elongated skull and partial wing structure against an arched architectural background.)

Step 1: Discovery and Historical Significance

Begin your journey by understanding the origins of our knowledge about Pteranodon. The first fossils were unearthed in 1870 by Othniel Charles Marsh during expeditions in the Smoky Hill Chalk deposits of western Kansas, USA. Initially misclassified due to an associated fish tooth (from Xiphactinus), Marsh correctly identified the toothless nature of the jaws and renamed the genus Pteranodon in 1876. This marked a pivotal moment in paleontology, as Pteranodon became one of the first pterosaurs discovered outside Europe and provided evidence of massive flying reptiles in North America.

Over the years, more than 1,200 specimens have been collected, primarily from the Niobrara Formation, making Pteranodon one of the best-represented pterosaurs in the fossil record. Key species include Pteranodon longiceps (with a long, backswept crest) and Pteranodon sternbergi (featuring a taller, upright crest). These finds, often preserved in marine sediments, highlight the animal’s coastal lifestyle. To replicate this discovery process in your studies, start by researching geological formations like the Smoky Hill Chalk—use online databases such as the Paleobiology Database to locate similar sites and understand sedimentary contexts.

For visual context, watch this educational video on Pteranodon discoveries: Pteranodon: The Giant Pterosaur | AMNH (search for American Museum of Natural History videos on Pteranodon for detailed fossil footage).

(A Pteranodon skeleton on display at an auction house, suspended in a flying pose to emphasize its impressive wingspan and aerodynamic form.)

Step 2: Anatomy and Physical Adaptations

Next, dissect the anatomy to appreciate Pteranodon’s flight capabilities. The skeleton in the image reveals a lightweight yet robust structure optimized for aerial life. Key features include:

- Skull and Crest: The elongated, toothless beak (up to 1 meter long in adults) was ideal for scooping fish from water surfaces. The prominent crest, varying by species and sex (larger in males for display), extended backward from the skull, potentially aiding in aerodynamics or species recognition. Measure this in replicas: crests could reach 75 cm in Pteranodon longiceps.

- Wings and Limbs: Wingspans ranged from 3.8 meters in females to over 7 meters in males, formed by a membrane stretched between an elongated fourth finger and the body. Hollow bones (walls as thin as 1 mm) reduced weight while maintaining strength—calculate the density: similar to modern birds but scaled up. The quadrupedal pose in the mount reflects ground movement; hind limbs were strong for launching into flight.

- Body Structure: A small torso with a large breastbone anchored powerful flight muscles. The pelvis differed by sex—narrower in males—indicating dimorphism. To study this hands-on, sketch the skeleton: note the fused bones in adults for maturity identification.

These adaptations made Pteranodon a master glider, soaring on thermals rather than constant flapping. Compare to modern albatrosses: both exploit ocean winds for energy-efficient travel.

(A flattened Pteranodon fossil mount in a museum case, displaying the full wingspread and preserved membrane impressions for anatomical study.)

Step 3: Habitat, Diet, and Behavior

Now, contextualize Pteranodon in its environment. Fossils from the Western Interior Seaway (a vast inland sea covering central North America) indicate a marine habitat. Pteranodon inhabited coastal regions, beaches, and river systems in present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, South Dakota, and Alabama. The warm, shallow seas teemed with fish, supporting its piscivorous diet—evidenced by fish remains in fossil stomachs.

Behaviorally, Pteranodon likely skimmed or dove for prey, landing on water to rest or feed. Sexual dimorphism suggests mating displays with crests. Nests on cliffs or islands protected eggs from predators. To model this, use simulation software or apps like 3D Dinosaur Simulator to visualize flight paths over ancient seas.

Explore a life reconstruction in this video: Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs | PBS (search for PBS or National Geographic clips on pterosaur behavior).

(Artistic depiction of Pteranodon soaring over stormy seas, catching fish mid-flight to illustrate its hunting strategy.)

Step 4: Evolutionary Context and Extinction

Pteranodon belongs to the Pteranodontoidea clade, evolving from smaller Triassic pterosaurs. Its size peaked due to abundant resources and lack of aerial competitors. Extinction coincided with the Cretaceous-Paleogene event 66 million years ago, likely from asteroid impact disrupting food chains.

Compare phylogenies: Use tools like Tree of Life Web Project to trace relations to birds (convergent evolution in flight).

(A vivid reconstruction of Pteranodon gliding at sunset over a prehistoric landscape, emphasizing its role in ancient ecosystems.)

Step 5: Modern Interpretations and Museum Visits

Today, Pteranodon inspires research on biomechanics—studies show it could launch from water using wings. Visit mounts at the Smithsonian, Yale Peabody, or Natural History Museum London. For tutorials, join paleontology workshops or use VR apps to “fly” as a Pteranodon.

In conclusion, this fossil embodies the wonders of prehistoric flight. Dive deeper with books like “Pterosaurs” by Mark Witton.

For an immersive experience, watch: The Pterosaur Exhibit | Tate Geological Museum.