Unveiling the Pachycephalosaurus: Anatomy, Evolution, and Paleontological Insights – A Comprehensive Guide

Description: A Detailed Exploration of the Pachycephalosaurus Dinosaur

Welcome to this in-depth tutorial on the Pachycephalosaurus, one of the most intriguing dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous period. This guide is designed for educators, students, paleontology enthusiasts, and anyone curious about prehistoric life. We’ll draw directly from detailed anatomical illustrations, such as the one featured here, to break down the dinosaur’s physical characteristics, behavioral hypotheses, evolutionary context, and the scientific challenges in reconstructing its form. By the end of this post, you’ll have a thorough understanding of this “thick-headed reptile” and how paleontologists interpret fossil evidence to bring it to life.

Step 1: Introduction to Pachycephalosaurus – Etymology and Overview

Pachycephalosaurus, pronounced “pak-ee-sef-uh-lo-saw-rus,” derives its name from Greek roots: “pachy” meaning thick, “cephalo” meaning head, and “saurus” meaning lizard or reptile. Translating to “thick-headed reptile,” this name aptly describes its most distinctive feature – a massively domed skull that could reach thicknesses of up to 25 centimeters (10 inches) in adults. As depicted in the illustration, this dinosaur is portrayed as the largest member of the Pachycephalosauridae family, often referred to as “bone-headed dinosaurs” due to their reinforced crania.

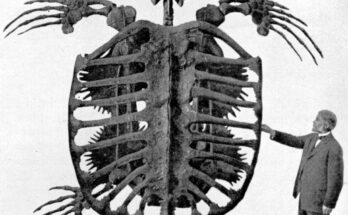

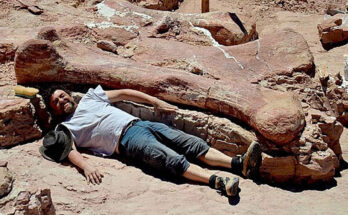

Fossils of Pachycephalosaurus have primarily been discovered in North America, specifically in formations like the Hell Creek Formation in Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming, dating back approximately 70-66 million years ago. This places it in the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous, just before the mass extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs. Unlike more complete skeletons of contemporaries like Tyrannosaurus rex or Triceratops, Pachycephalosaurus remains are fragmentary, consisting mostly of skull domes and partial cranial elements. This scarcity has made full-body reconstructions, like the one in the image, reliant on comparative anatomy with related species such as Stegoceras or Prenocephale.

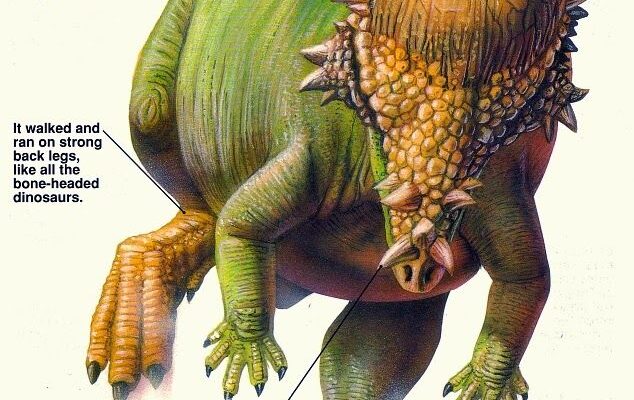

In the illustration, the dinosaur is shown in a dynamic, forward-leaning pose, emphasizing its bipedal locomotion. Its green and yellowish-brown coloration is artistic, as skin impressions are rare for this group, but it evokes a forested or semi-arid environment typical of its habitat. This visual serves as an educational tool to highlight key features, which we’ll dissect in the following sections.

Step 2: Analyzing the Skull – The Defining Feature

The skull is the star of any Pachycephalosaurus depiction, and the image labels it prominently as having “a much more bumpy skull than Stegoceras.” Stegoceras, a smaller relative, had a smoother dome, whereas Pachycephalosaurus exhibited a rougher, more ornamented surface with nodes, spikes, and ridges.

- The Dome Structure: At the top of the head, the huge dome is composed of thickened frontal and parietal bones. This wasn’t just for show; paleontologists hypothesize it served multiple purposes. One leading theory is head-butting behavior, similar to modern bighorn sheep, where males might have clashed domes during mating rituals or territorial disputes. The dome’s internal structure, revealed through CT scans of fossils, shows dense bone with vascular channels, suggesting it could withstand impacts without fracturing. In the illustration, the dome is rendered in a golden hue, textured to show its bumpy, almost furry appearance from keratinous coverings or skin folds.

- Bumps and Spikes on the Snout: As noted in the image, “It had bumps and spikes on its snout, too.” These adornments, including short horns or nodes around the nasal region and squamosal bones (the rear sides of the skull), add to its rugged look. These features might have been used for display, species recognition, or even minor defensive purposes. The snout itself is short and robust, equipped with small, leaf-shaped teeth suited for a herbivorous diet.

- Comparison to Other Bone-Headed Dinosaurs: The image contrasts it with Stegoceras, emphasizing the bumpier texture. This highlights evolutionary divergence within the family: smaller species like Stegoceras (about 2-3 meters long) had domes for agility in head-butting, while the larger Pachycephalosaurus (up to 4.5-5 meters long and weighing 450 kg) might have used its size for more forceful encounters.

To visualize this in a tutorial setting, imagine dissecting a fossil skull: Start by identifying the dome’s apex, then trace the squamosal spikes downward. Use 3D modeling software like Blender or visit museum exhibits (e.g., at the Royal Tyrrell Museum) for hands-on learning.

Step 3: Body Structure and Locomotion – From Limbs to Tail

Moving beyond the head, the illustration provides a full-body view, labeling various anatomical parts to educate on its overall build.

- Strong Back Legs: “It walked and ran on strong back legs, like all the bone-headed dinosaurs.” Pachycephalosaurus was obligatorily bipedal, meaning it moved primarily on its hind limbs. The legs are depicted as muscular and pillar-like, with three-toed feet equipped with claws for traction. This setup allowed for bursts of speed, potentially up to 25-30 km/h (15-18 mph), useful for evading predators like T. rex. The femur (thigh bone) is robust, supporting a semi-erect posture, as shown in the forward-leaning stance.

- Short Arms: “It only had short arms.” The forelimbs are comically diminutive compared to the body, with five-fingered hands (though some digits were reduced). These arms likely served minimal functions, perhaps for grasping foliage or balance during movement. In the image, they’re positioned forward, claws visible, underscoring their limited reach.

- Overall Body Form: The torso is compact, with a relatively short neck transitioning into the domed head. The tail, though not heavily labeled, appears stiff and counterbalancing, aiding in stability. Scales or osteoderms (bony skin plates) are implied in the textured skin rendering, providing some protection.

Reconstruction challenges are highlighted: “Scientists have tried to figure out what this dinosaur’s body looked like. They have never found a whole skeleton, so it is hard to tell exactly.” This is a key tutorial point – paleontology relies on phylogenetic bracketing, comparing to relatives like ornithopods or other marginocephalians. For instance, body proportions are inferred from Dracorex or Stygimoloch, sometimes considered juvenile forms of Pachycephalosaurus itself (a debated “ontogenetic series” hypothesis).

Step 4: Diet, Behavior, and Ecology – Lifestyle Insights

The image concludes with dietary notes: “Bone-headed dinosaurs probably searched for leaves and fruit to eat.” As herbivores, Pachycephalosaurs were likely browsers, using their beaked mouths to strip vegetation from low-lying plants in floodplain forests.

- Feeding Habits: With heterodont teeth (varied shapes), they could process fibrous plants, seeds, or fruits. No direct gut contents have been found, but comparisons to modern herbivores suggest a mixed diet avoiding tough conifers.

- Behavioral Hypotheses: The domed head suggests intra-species combat, but alternatives include flank-butting or display. Socially, they might have lived in herds, as evidenced by bone beds of related species.

- Habitat and Predators: Inhabiting what is now the Western Interior of North America, they coexisted with diverse fauna. Predation pressure from tyrannosaurids would have favored their agile build.

For a tutorial exercise: Simulate a dig site by sketching fossil fragments and reconstructing the full animal, discussing uncertainties like soft tissue (e.g., did the dome have a keratin sheath?).

Step 5: Paleontological Significance and Modern Research

Pachycephalosaurus exemplifies the iterative nature of science. First described in 1943 by Barnum Brown and Erich Schlaikjer, ongoing studies use finite element analysis (FEA) to model head impacts, supporting or refuting butting theories. Recent finds, like a 2020 juvenile specimen, refine our understanding.

In educational contexts, use this illustration as a starting point for STEM activities: Calculate dome volume using math (volume of a sphere segment: V = (πh²(3r – h))/3), or model evolutionary pressures in biology classes.

Conclusion: Why Study Pachycephalosaurus Today?

This “biggest bone-headed dinosaur” offers lessons in adaptation, evolution, and the limits of fossil evidence. By examining illustrations like this, we bridge gaps in knowledge, inspiring future discoveries. For further reading, consult resources like “The Dinosauria” by Weishampel et al., or visit online databases such as the Paleobiology Database.

If you’re creating a model or diorama, start with the skull dome as your anchor – it’s the feature that defines this enigmatic reptile. Share your reconstructions in the comments below!