The Colossal Scale of Sauropods: Exploring a Massive Dinosaur Vertebra Exhibit and the Awe of Prehistoric Giants

Description: An In-Depth Educational Exploration

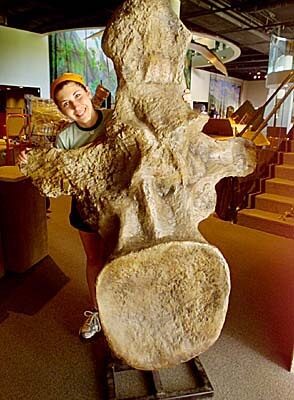

Embark on a captivating tutorial-style journey into the world of sauropod dinosaurs through this detailed guide, inspired by a striking museum photograph of a young visitor enthusiastically posing beside an enormous fossilized vertebra. The image captures pure excitement: a smiling person in a light green shirt, orange headband, black shorts, and sneakers stands with arms outstretched, embracing the side of a towering, rugged vertebra mounted on a black pedestal. This single bone, with its textured, honeycomb-like internal structure (pneumatic cavities for lightweight strength), broad centrum, and prominent neural spine and processes, dwarfs the visitor – the vertebra’s height exceeds the person’s full stature, emphasizing the unimaginable size of the dinosaur it once supported. Set in a modern museum hall with interpretive murals of prehistoric landscapes, display cases, and a staircase in the background, this exhibit vividly illustrates why sauropods were the largest land animals ever to walk the Earth. Ideal for educators, students, families, or anyone fascinated by paleontology, this guide breaks down the exhibit step-by-step, from visual details to scientific insights, helping you appreciate these Jurassic and Cretaceous behemoths.

Step 1: Visual Analysis of the Exhibit – Capturing the Sense of Scale and Wonder

Begin your tutorial by examining the photograph closely, as it masterfully conveys the overwhelming scale of sauropod anatomy. The focal point is a single dorsal (back) vertebra, likely from a titanosaur or diplodocid sauropod, displayed vertically on a sturdy metal stand for optimal viewing. The bone’s surface is rough and earthy brown, preserved with natural fossil texture, showing deep excavations and cavities – adaptations that made massive bodies feasible by reducing weight while maintaining strength.

The visitor’s joyful pose – arms wrapped around the vertebra’s side, head tilted with a wide grin – provides perfect human scale: the centrum (main body) alone is wider than the person’s torso, and the entire bone stands taller than an average adult (estimated 1.5–2 meters or 5–6.5 feet high). This interactive moment highlights why such exhibits are designed for touch or close proximity in some museums (often casts for safety). The background features immersive elements: a large mural depicting lush prehistoric vegetation, glass cases with smaller fossils, and ambient lighting that evokes a sense of discovery. Scattered interpretive panels and the hall’s open layout suggest a major natural history institution focused on engaging visitors with dinosaur evolution.

Tutorial tip: Photos like this are powerful educational tools – use them to discuss proportions. Compare the vertebra’s size to everyday objects: it’s larger than a refrigerator, underscoring how sauropods needed such enormous vertebrae to support necks up to 15 meters (50 feet) long and bodies weighing 50–100 tons.

Step 2: Historical Context – The Discovery and Display of Giant Sauropod Fossils

Trace the origins of sauropod vertebra exhibits in this historical tutorial segment. Sauropods, meaning “lizard-footed,” dominated the Late Jurassic to Late Cretaceous (about 160–66 million years ago), with fossils primarily from formations like the Morrison (USA) or Patagonia (Argentina). Iconic discoveries include Apatosaurus and Diplodocus in the late 1800s during the “Bone Wars” by O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope, fueling early museum displays.

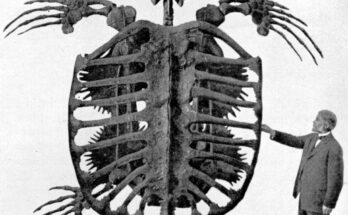

Larger titanosaurs like Argentinosaurus (discovered 1987 in Argentina) and Dreadnoughtus (2014, also Argentina) pushed size limits, with vertebrae over 1.5 meters tall – matching the exhibit’s scale. Many displayed vertebrae are high-quality casts of originals (stored for research), allowing safe public interaction. Museums like the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHMLAC), or Perot Museum of Nature and Science often feature such isolated bones in “World’s Largest Dinosaurs” exhibits to highlight biomechanics.

Key milestone: Temporary exhibits (e.g., AMNH’s 2011 “The World’s Largest Dinosaurs”) showcased Mamenchisaurus or Argentinosaurus vertebrae, inspiring poses like the one in the image. Modern displays emphasize accuracy, using CT scans to reveal internal air sacs.

Tutorial exercise: Research museum catalogs – many giant vertebrae come from Patagonia, where erosion exposes massive bones, revolutionizing our understanding of dinosaur growth and ecosystems.

Step 3: Physical Characteristics – Anatomy Breakdown of a Sauropod Vertebra

Dissect the vertebra anatomically, using the image as a virtual specimen. Sauropod vertebrae are engineering marvels:

- Centrum: The large, spool-shaped base (visible as the broad lower portion) bore immense weight, often opisthocoelous (convex front, concave back) for flexibility.

- Neural Arch and Spine: The tall upper structure protected the spinal cord; prominent processes (transverse, diapophyses) anchored massive muscles and ribs.

- Pneumaticity: Honeycomb cavities (clearly seen in cross-section) housed air sacs, reducing density by up to 50–60% – crucial for giants like Argentinosaurus (estimated 70–100 tons).

- Size Indicators: This vertebra likely from the mid-dorsal series; cervical (neck) ones were longer, caudal (tail) smaller.

In the photo, the person’s hug spans only part of the centrum, illustrating how a full skeleton required dozens of such bones. Titanosaurs had especially robust vertebrae for supporting enormous guts and long necks for high browsing.

Tutorial tip: Compare to human vertebrae – ours are tiny and solid; sauropods evolved extreme pneumatization from bird-like respiratory systems, allowing sizes impossible for mammals.

Step 4: Scientific Facts and Insights – Paleobiology of the Largest Land Animals

Advance your understanding with paleobiology insights. Sauropods like Argentinosaurus or Patagotitan (one of the longest at 37 meters/122 feet) lived in herds, consuming hundreds of kilograms of plants daily via peg-like teeth and gastric mills (stones for grinding).

Key facts:

- Growth Rates: Rapid juvenile growth (up to 2 tons/year) via high metabolism, evidenced by bone histology.

- Adaptations: Long necks for sweeping vegetation without moving bodies; pillar-like legs for support.

- Environment: Thrived in floodplains with abundant ferns and conifers; air sacs aided cooling and oxygen delivery.

- Debates: Were they warm-blooded? Evidence from bone growth rings suggests yes, partially.

Exhibits like this vertebra demonstrate biomechanical limits – beyond certain sizes, hearts couldn’t pump blood to brains in raised necks (though they likely held heads low).

Tutorial exercise: Model forces using simple physics – calculate compressive strength needed for a 100-ton body on four legs.

Step 5: Cultural and Educational Significance – Inspiring the Next Generation

Conclude by reflecting on why this exhibit resonates. The visitor’s enthusiastic pose captures the universal thrill of dinosaurs, sparking STEM interest in children. Such displays humanize science, showing Earth’s ancient giants were real, not monsters.

Cultural impact: From Jurassic Park to museum visits, sauropods symbolize wonder. Interactive elements (touchable casts) make learning tactile.

For educators: Replicate the pose in classrooms with models; discuss extinction (asteroid impact ended their reign).

In summary, this massive sauropod vertebra exhibit embodies the grandeur of prehistoric life. Follow this guide to unlock its secrets – whether visiting a museum or exploring online, the scale will astonish. Plan your trip to see similar fossils at institutions like AMNH or NHMLAC, and delve into resources like peer-reviewed titanosaurs studies for more. The age of giants lives on!