Understanding Wind Effects on Buildings: How Trees and Shrubs Redirect Pressure and Create Comfortable Outdoor Spaces

Description:

In architectural and landscape design, wind is one of the most influential environmental forces affecting building performance, occupant comfort, energy efficiency, and structural longevity. Uncontrolled wind can create unwanted pressure on walls and roofs, accelerate heat loss, generate uncomfortable drafts, and even contribute to noise and dust issues. Strategic use of vegetation—particularly trees and shrubs—offers a natural, sustainable solution to modulate wind behavior, relieve pressure, and deflect airflow away from vulnerable areas.

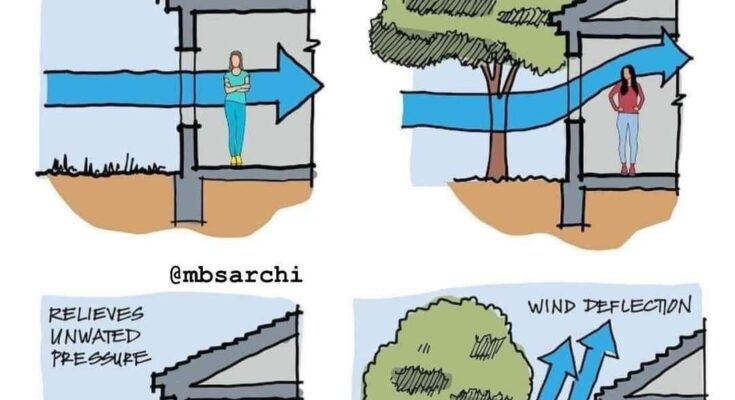

This detailed tutorial, inspired by principles from @mbsarchi, breaks down four key scenarios illustrating wind effects around simple structures (such as porches, verandas, or single-story buildings). Each diagram shows how wind interacts with the building—with and without vegetation—and demonstrates practical strategies for mitigation. These concepts are applicable to residential, commercial, and urban design projects, especially in windy regions like coastal areas, plains, or high-elevation sites.

Core Principles of Wind Interaction with Buildings

- Direct pressure: Horizontal wind strikes vertical surfaces, creating positive pressure on the windward side and negative (suction) on the leeward side.

- Turbulence and eddies: Sharp edges, overhangs, and open structures amplify swirling airflow, increasing discomfort and potential damage.

- Aerodynamic deflection: Trees and shrubs act as porous barriers that slow, lift, and redirect wind, reducing velocity in the protected zone by 30–80% depending on density and placement.

- Permeability matters: Dense, solid barriers can cause downdrafts; moderately porous plantings (40–60% density) produce smoother, more effective wind shadows.

Breakdown of the Four Scenarios (Tutorial Style)

- Uncontrolled Wind – Direct Unwanted Pressure (Top Left) Without any vegetation, prevailing wind hits the building broadside, creating strong horizontal pressure against the wall and under the roof overhang.

- The figure stands uncomfortably in the full force of the wind.

- This configuration leads to higher heating/cooling loads, structural stress on connections, and unpleasant outdoor conditions.

- Design lesson: Exposed elevations facing dominant winds require immediate mitigation.

Here are real-world examples of buildings experiencing strong direct wind pressure and the resulting challenges:

- Tree Without Strategic Placement – Wind Still Enters (Top Right) A single tree placed too close or directly in line allows wind to flow around and under the canopy, still directing significant airflow toward the structure.

- The wind curves downward and enters the open area beneath the tree.

- While some reduction occurs, the building remains exposed to drafts.

- Design lesson: Tree placement must consider mature canopy height, trunk clearance, and distance from the building (ideally 1.5–3× canopy height upwind).

- Low Shrub Barrier – Relieves Unwanted Pressure (Bottom Left) A dense, low-to-medium height shrub hedge planted upwind creates a ground-level windbreak.

- Wind is forced upward and over the vegetation, forming a recirculating eddy (shown with the curved arrow) that significantly reduces pressure on the lower wall and porch.

- The figure experiences much calmer conditions.

- Design lesson: Shrubs are excellent for protecting entrances, patios, and lower facades; choose wind-tolerant, evergreen species (e.g., junipers, boxwood, or privet) for year-round effect.

Real examples of effective shrub and hedge windbreaks around homes:

- Well-Placed Tree – Effective Wind Deflection (Bottom Right) A mature tree positioned at an optimal distance upwind lifts and deflects the wind over the building.

- Airflow rises smoothly over the canopy and descends farther downwind, creating a large sheltered zone.

- The seated figure enjoys a calm, protected microclimate.

- Design lesson: This is the ideal outcome—use taller trees for broader protection; combine with shrubs for layered defense.

For visual inspiration, here are examples of mature trees successfully deflecting wind in landscape settings:

Advanced Application Tips

- Layered planting: Combine low shrubs (front), medium trees (middle), and tall trees (rear) for maximum depth and turbulence reduction.

- Porosity & spacing: Aim for 50% density in windbreaks to avoid damaging downdrafts behind solid barriers.

- Site-specific analysis: Use local wind rose data to determine prevailing direction; test with wind modeling software or physical models.

- Co-benefits: Beyond wind control, vegetation provides shade, privacy, noise reduction, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration.

- Common pitfalls: Planting too close (causing branch damage or root issues), using non-wind-tolerant species, or creating impermeable walls that funnel wind elsewhere.

Mastering these wind modulation techniques allows designers to transform exposed, uncomfortable sites into resilient, livable spaces. Whether you’re planning a new home, retrofitting an existing property, or designing public landscapes, thoughtful vegetation placement is one of the most cost-effective and eco-friendly tools available.

Have you implemented windbreaks on your site? What challenges have you faced with wind in your region? Share your projects, photos, or questions in the comments—we’d love to discuss! 🌬️🌳 #ArchitecturalDesign #LandscapeArchitecture #SustainableDesign #WindMitigation #PassiveCooling