Introduction to Whale Evolution

Whales are among the most captivating examples of evolutionary change. Their ancestors were once land-dwelling mammals that roamed the Earth millions of years ago. Over time, through a series of gradual anatomical and behavioral changes, these creatures adapted to aquatic life, eventually evolving into the modern whales we know today. This transition involved modifications to their limbs, spine, skull, and respiratory system to enable efficient swimming, deep diving, and underwater feeding.

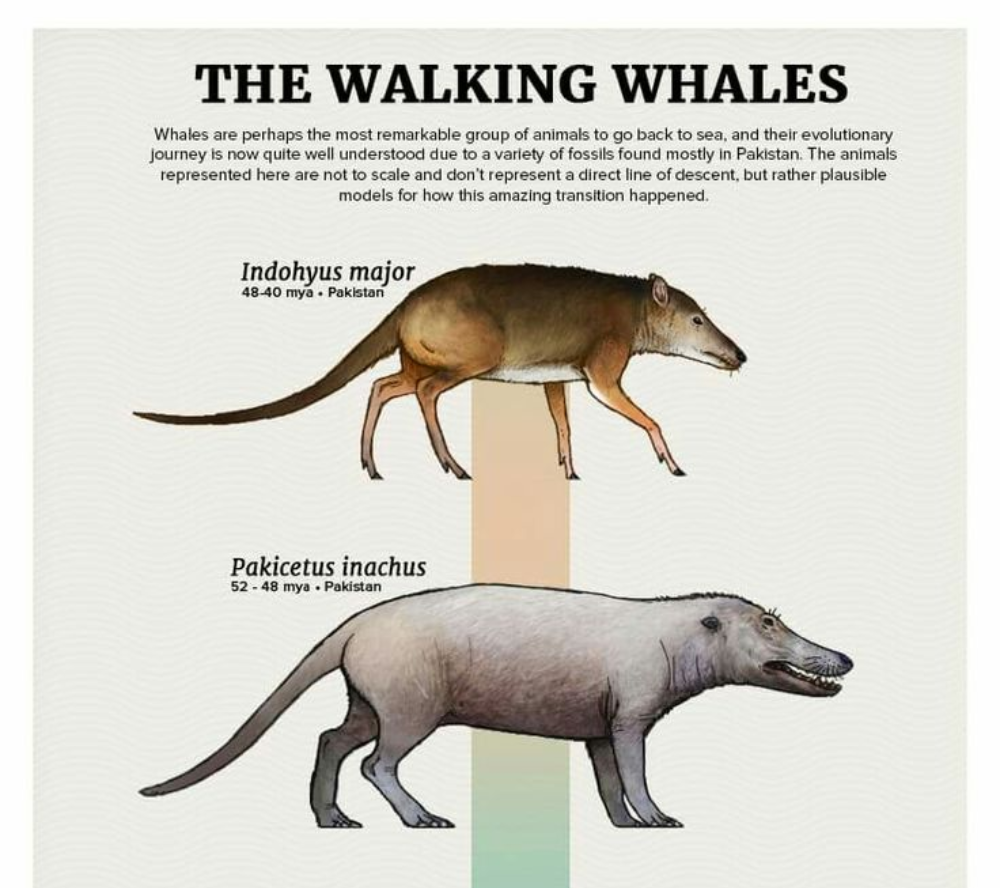

The image shows five key transitional species, each representing a critical step in whale evolution. Although the creatures depicted are not direct ancestors of one another, they represent plausible evolutionary models that help scientists understand how the transition from land to sea occurred.

1. Indohyus major (48–40 million years ago)

-

Location: Pakistan

-

Description:

Indohyus is one of the earliest known relatives of modern whales. It was a small, deer-like mammal that resembled a modern-day chevrotain (mouse deer). Indohyus is believed to have been a semi-aquatic creature that waded in shallow waters to avoid predators and find food. Its dense bones helped it stay submerged in water, a trait still seen in modern whales. -

Key Adaptations:

-

Thickened bones (pachyostosis) for stability in water

-

Elongated tail for better movement in shallow waters

-

Early signs of auditory adaptations for hearing underwater

-

2. Pakicetus inachus (52–48 million years ago)

-

Location: Pakistan

-

Description:

Pakicetus is one of the first known cetaceans (the group of mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises). It was a land-dwelling predator with long legs and a wolf-like body. Despite its terrestrial nature, Pakicetus had ear structures adapted for hearing underwater, suggesting it spent significant time near or in water. -

Key Adaptations:

-

Well-developed limb bones for walking on land

-

Sharp teeth suited for catching fish and small prey

-

Early development of specialized ear bones for underwater hearing

-

3. Ambulocetus natans (47–41 million years ago)

-

Location: Pakistan

-

Description:

Ambulocetus, whose name means “walking whale that swims,” was an amphibious predator. It had elongated limbs and webbed feet, allowing it to both walk on land and swim in water. Its body resembled that of a large otter or crocodile, with a long snout and powerful jaws. -

Key Adaptations:

-

Powerful limbs for swimming and walking

-

Webbed feet for propulsion in water

-

Flexible spine for enhanced swimming motion

-

Nostrils positioned near the snout, an early adaptation for aquatic breathing

-

4. Rodhocetus kasrani (48–40 million years ago)

-

Location: Pakistan

-

Description:

Rodhocetus was a more advanced aquatic mammal, with shorter limbs and a streamlined body. Its pelvis was no longer attached to the spine, indicating that it could not walk efficiently on land but was a skilled swimmer. Its large, sharp teeth suggest a carnivorous diet. -

Key Adaptations:

-

Reduced hind limbs for better swimming

-

Long, powerful tail for propulsion

-

Nostrils moving further back along the skull, a precursor to the blowhole

-

5. Protocetus atavus (45 million years ago)

-

Location: Egypt

-

Description:

Protocetus was almost fully aquatic. Its nostrils had migrated to the top of its head, forming a primitive blowhole. Its body was streamlined, and its limbs were nearly vestigial. Protocetus likely swam using a combination of tail and limb movements. -

Key Adaptations:

-

Blowhole positioned further back on the skull

-

Hind limbs reduced and no longer weight-bearing

-

Fully developed tail fluke for efficient swimming

-

Evolutionary Significance

The evolutionary journey of whales is one of the most well-documented examples of macroevolution. Fossils like Indohyus, Pakicetus, and Ambulocetus provide compelling evidence of the gradual transition from land to sea. The anatomical changes observed in these species — such as the development of a blowhole, streamlined body, and tail fluke — reflect natural selection’s role in shaping organisms to thrive in new environments.

Modern whales (baleen and toothed whales) retain traces of their terrestrial ancestry. For example:

-

Vestigial hip bones in whales are remnants of their land-dwelling ancestors.

-

Their method of giving birth and nursing underwater points to mammalian origins.

-

The complex echolocation system in toothed whales reflects adaptations for life in deep water.

Why Pakistan and Egypt?

Most of these critical fossils have been found in Pakistan and Egypt, which were part of the Tethys Sea during the Eocene epoch (around 50 million years ago). The shallow, warm waters of the Tethys Sea provided an ideal environment for early whale ancestors to evolve and adapt to aquatic life.

Conclusion

The transition from walking land mammals to fully aquatic whales is a fascinating story of adaptation and survival. The evolutionary stages depicted in the image — from Indohyus to Protocetus — highlight how natural selection can drive profound anatomical and behavioral changes over millions of years. Whales are living evidence of Earth’s dynamic evolutionary history, reminding us of the deep connection between land and sea.