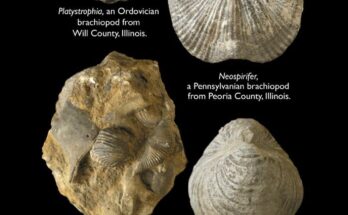

A Detailed Tutorial on Identifying Miocene to Pleistocene Fish and Cartilaginous Fossils from Amelia Island, Florida

Description:

This comprehensive guide serves as both an educational tutorial and a visual reference for collectors, students, and amateur paleontologists interested in the diverse fish and cartilaginous fossils commonly found along the beaches of Amelia Island, Florida. The image showcases a representative selection of vertebrate fossils recovered from the island’s shoreline, all originating from Miocene to Pleistocene deposits (approximately 20 million to ~11,700 years ago). These specimens are derived primarily from the Hawthorn Group (Middle Miocene) and overlying Pliocene–Pleistocene sands and gravels, reflecting ancient shallow marine and nearshore environments that supported rich communities of sharks, rays, bony fish, and other vertebrates.

Amelia Island’s fossils are exposed through modern beach erosion, wave action, and occasional dredging, making the area a popular (and accessible) location for fossil hunting. Always obtain the required Florida vertebrate fossil collecting permit before searching for or removing vertebrate material from state beaches. This tutorial walks through each specimen type shown in the image, providing identification criteria, anatomical context, geological background, and practical tips for recognition in the field.

Geological and Paleoecological Context

The fossils illustrated here come from sedimentary layers deposited during a period of fluctuating sea levels. During the Miocene (~23–5 million years ago), northern Florida was covered by warm, shallow seas teeming with diverse marine life. Shark and ray remains are particularly abundant because their cartilaginous skeletons are poorly preserved, but teeth, vertebrae, dermal denticles, and calcified structures (such as ray mouthplates and spines) fossilize readily due to their phosphate-rich composition.

By the Pleistocene (Ice Age, ~2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), sea-level changes continued to rework older material into beach sands. The result is a mixed assemblage of fossils ranging in age from Middle Miocene to late Pleistocene, often found together on modern beaches.

Step-by-Step Specimen Analysis

- Fish Vertebrae (Top row, center and right – rounded disc and oval/cylindrical forms) These are centra (vertebral bodies) from bony fish (teleosts).

- Appearance: Circular to slightly oval discs with concentric growth rings on the articular surface (resembling tree rings) and a central perforation (notochord canal). The example on the left shows clear concentric layers; the smaller, more cylindrical piece shows typical side-wall texture.

- Size range: Commonly 0.5–2 cm in diameter.

- Identification tips: True bony fish vertebrae are usually rounder and more symmetrical than ray vertebrae. Compare to modern drum, croaker, or snapper vertebrae.

- Paleoecology: These fish lived in coastal and estuarine waters.

- Field tip: Look for smooth, rounded edges and concentric patterns—avoid confusing them with modern shell fragments or concretions.

- Shark Vertebrae (Top row, left – large circular disc; also lower examples) These centra belong to cartilaginous fish (sharks, typically lamniform or carcharhiniform groups).

- Appearance: Thick, circular to slightly oval discs with radiating calcified lamellae (spokes) visible on the cut or worn surface. The large example displays prominent concentric growth bands and a central nutrient foramen.

- Size range: 1–5+ cm diameter (larger ones often from big species like great white relatives or extinct lamnids).

- Identification tips: Shark vertebrae are typically more circular than ray vertebrae (which tend to be oval or rectangular). They lack the strong dorso-ventral compression seen in ray centra.

- Paleoecology: Apex predators in Miocene–Pleistocene seas.

- Field tip: Heavy and dense; often darker or amber-colored due to phosphatization.

- Fish Skull Piece (Middle row, left – comb-like or ridged fragment)

- Appearance: Elongated, flat fragment with parallel ridges or tooth-like projections along one edge, likely part of a pharyngeal jaw, dermal bone, or skull roof.

- Identification tips: Compare to modern bony fish skull elements (e.g., drum or sheepshead grinding plates). The ridged texture is characteristic of crushing or grinding surfaces.

- Field tip: These are less common than vertebrae but distinctive when found—look for the organized, repetitive ridge pattern.

- Ray Mouthplate (Middle row, center – broad, comb-like plate)

- Appearance: Wide, flat dental plate with parallel rows of small, hexagonal or pavement-like teeth fused into a crushing surface. The example shows a clear “comb” or ridged structure.

- Anatomy note: Modern rays (especially Myliobatidae – eagle rays, cownose rays) have upper and lower dental plates used for crushing shellfish and crustaceans. Fossil plates are often found fragmented.

- Identification tips: Look for the tessellated (tile-like) tooth arrangement and flat, broad shape. Distinguished from shark teeth by lack of pointed cusps.

- Paleoecology: Bottom-dwelling durophagous (shell-crushing) feeders in shallow marine settings.

- Ray Mouthplate Fragment (Lower left – smaller, partial section)

- Appearance: Broken portion of a similar crushing plate, showing partial rows of hexagonal teeth.

- Identification tips: Same criteria as above—focus on the pavement texture and lack of enameloid shine typical of shark teeth.

- Ray Tail Spine (Lower right – elongated, serrated rod)

- Appearance: Long, slender, dagger-like structure with backward-facing serrations along one or both edges. The example is well-preserved with clear barbs.

- Anatomy note: Stingray tail spines (barbs) are modified dermal denticles used for defense. They detach periodically and are shed/replaced like shark teeth.

- Identification tips: Serrated edges are diagnostic. Compare to modern stingray barbs (Dasyatidae, Myliobatidae).

- Field tip: Often black or dark brown; sharp and pointed—handle carefully.

Practical Collecting and Identification Tips

- Best search strategy: Walk the low-tide line after storms, especially near inlets or river mouths. Focus on gravelly patches and shell hash.

- Preservation: Most specimens are phosphatized (black/dark brown) or permineralized. Colors vary from tan to black depending on iron and manganese staining.

- Common confusions: Avoid mistaking modern bone, shell, or concretions for fossils. Test density—fossils are heavier.

- Further study: Compare with online resources (e.g., Florida Museum of Natural History shark tooth guides) or local museum collections. Photograph finds in place and note GPS coordinates for scientific value.

These fossils offer a tangible window into Florida’s ancient marine ecosystems, showcasing the diversity of cartilaginous and bony fishes that once swam in waters now lapping at Amelia Island’s shores. Whether you’re a beginner beachcomber or an experienced collector, understanding these specimens enhances every fossil-hunting trip. Happy hunting—and always collect responsibly!

(Photographs courtesy of www.fossilguy.com – used with permission for educational purposes.)