Exploring Cretaceous Marine Fossils: A Detailed Guide to Xiphactinus, Mosasaurs, and Ancient Sea Ecosystems in Museum Displays

Introduction to Cretaceous Marine Fossils

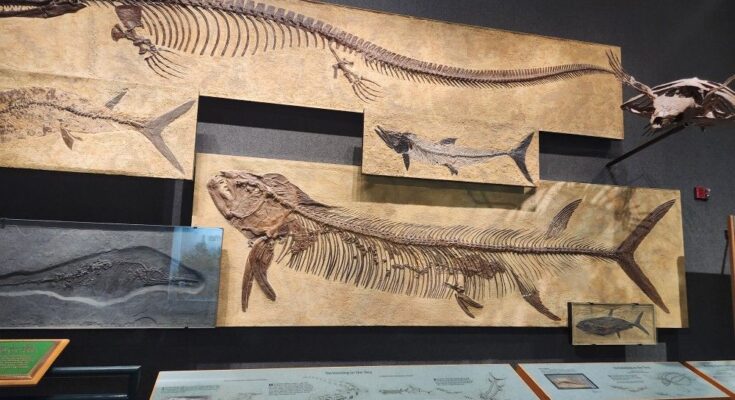

The image depicts a captivating wall-mounted exhibit of fossilized marine creatures from the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 100 to 66 million years ago, showcased in a museum environment with dark walls, informational panels, and descriptive plaques below. This display highlights life in the Western Interior Seaway, a vast inland sea that once divided North America into two landmasses. Prominent specimens include a large Xiphactinus audax (a predatory fish), a mosasaur (an extinct marine reptile), and smaller fish like Gillicus arcuatus, illustrating the dynamic predator-prey relationships of this ancient ocean. In this professional tutorial-style guide, we’ll break down the exhibit step by step: from visual identification and anatomical analysis to historical discoveries, ecological insights, and paleontological significance. Ideal for educators, students, or enthusiasts, this post serves as a virtual tour, preparing you for museum visits or deeper research into Mesozoic marine paleontology.

Begin your analysis with the overall layout: The fossils are embedded in sedimentary rock slabs, preserved in flattened profiles typical of lagerstätten deposits like the Niobrara Chalk Formation in Kansas. The top specimen is an elongated mosasaur skeleton, the middle row features smaller fish, and the bottom displays a massive Xiphactinus, with additional elements like a possible ammonite or turtle fossil on the lower left. These mounts emphasize the seaway’s biodiversity, where reptiles and fish coexisted in a subtropical marine habitat. The informational panels, such as the central one titled “Swimming in the Sea,” provide diagrams of swimming mechanics and evolutionary adaptations, enhancing educational value.

Step 1: Identifying and Analyzing the Xiphactinus audax – The Dominant Predator

Start with the largest fossil at the bottom: This is a nearly complete skeleton of Xiphactinus audax, often called the “bulldog fish” for its protruding lower jaw and formidable teeth. Measuring up to 4-6 meters (13-20 feet) in length, this teleost fish was a swift apex predator, capable of swallowing prey whole. In the image, observe the streamlined body, long vertebral column (over 100 vertebrae for flexibility), and heterocercal tail fin for powerful propulsion. The skull features sharp, conical teeth in a wide gape, ideal for ambushing smaller fish.

To dissect like an anatomical tutorial: The pectoral and pelvic fins are small but sturdy, supporting burst swimming speeds estimated at 50-60 km/h (30-37 mph). Note the preserved gut region – famous specimens, like the “fish-within-a-fish” discovered in 1952 by George F. Sternberg, show Xiphactinus with undigested Gillicus inside, indicating death from overambitious meals. In museum prep, these fossils are excavated from chalk beds, cleaned with acetic acid, and mounted on plaques for wall display to simulate swimming poses.

Compare to modern analogs: Think swordfish or tarpon, but scaled up with more aggressive dentition. For researchers, CT scans reveal internal structures, such as the swim bladder for buoyancy control in shallow seas.

Step 2: Examining the Mosasaur Skeleton – Reptilian Rulers of the Waves

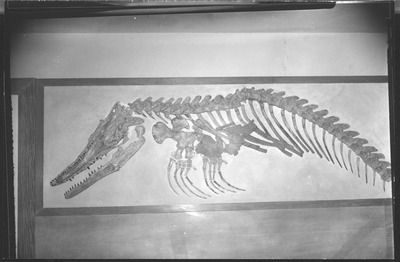

Shift focus to the top specimen: This is likely a mosasaur, such as Platecarpus or Clidastes, extinct squamate reptiles that dominated Cretaceous seas. Reaching lengths of 3-5 meters (10-16 feet) for smaller species, mosasaurs evolved from land lizards, developing flipper-like limbs for aquatic locomotion. In the photo, the elongated skull with double rows of pterygoid teeth for gripping slippery prey stands out, along with the serpentine vertebral column and reduced hind limbs.

Tutorial breakdown: The ribcage is narrow for streamlined swimming, and the tail is flattened for sculling propulsion, allowing speeds up to 30 km/h (19 mph). Fossils often preserve skin impressions showing scales and possible color patterns. Preparation involves removing matrix with pneumatic tools, revealing details like the quadrate bone for wide jaw opening.

Ecologically, mosasaurs were top predators, preying on fish like Xiphactinus, ammonites, and even other reptiles. Their viviparous birth (live young) is inferred from fossil embryos. In displays, they’re often positioned above fish to evoke food chain dynamics.

Step 3: Detailing the Smaller Fish and Supporting Fossils – Ecosystem Diversity

Examine the middle and side elements: The smaller skeletons are likely Gillicus arcuatus or similar ichthyodectids, about 1-2 meters (3-6 feet) long, with slender bodies and upturned mouths for filter-feeding or mid-water hunting. Their forked tails and fine scales indicate agile swimmers in open water.

On the lower left, a flattened fossil may be a protostegid turtle or ammonite shell, adding to the seaway’s invertebrate and reptile diversity. These specimens highlight mass mortality events, where anoxic conditions preserved entire assemblages.

Analytical tip: Use magnification to spot details like otoliths (ear stones) for age determination or stomach contents for diet reconstruction.

Step 4: Historical Discoveries and Fossil Record

Trace the origins like a historical tutorial: Xiphactinus was first described in 1870 by Joseph Leidy from Kansas fossils. Key finds include Sternberg’s 1952 “fish-within-a-fish” at the Sternberg Museum in Hays, Kansas, measuring 4.2 meters (14 feet). Mosasaurs were discovered in 1764 near Maastricht, Netherlands, initially mistaken for crocodiles.

Fossils primarily come from the Niobrara Formation, excavated using grid mapping and plaster jacketing. Museums like the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), Sternberg, and Denver Museum of Nature & Science feature these in halls dedicated to Mesozoic seas.

Step 5: Behavioral, Ecological, and Modern Insights

Reconstruct behaviors: Xiphactinus ambushed prey in schools, while mosasaurs used stealth and speed, possibly hunting in packs. The seaway teemed with life, from plankton to megafauna, ending with the K-Pg extinction event.

Today, these exhibits educate on climate change parallels, as the seaway formed due to high sea levels from warming. For visitors, note reconstructions – many fins are inferred from impressions.

In conclusion, this exhibit transports us to a vanished sea, fostering appreciation for evolutionary history. Use this guide to enhance your next museum experience or inspire paleontological studies.